Peanut news

Over at National Public Radio, a story of an inveterate tinkerer who built a better peanut sheller (and much else besides). Not the kind of thing I personally need. I enjoy creating masses of biodegradable debris while I snack. In Africa, however, the hero of the story:

noticed African women shelling thousands of peanuts by hand. It was slow, painful work that made their fingers bleed. Before he left the country, he made a promise that he was going to send them back a peanut sheller. But he ran into a problem. “When I came back to America to buy it, it didn’t exist,” he says.

Bottom line. He made it, it works. And rather than simply give it away, he sells the plans.

That makes farmers investors in a minifactory. They get a set of instructions and concrete molds that allow them to build their own … shellers.

And here it is in action. I like that they don’t bother separating the debris from the nuts, which is easy and satisfying to do by hand.

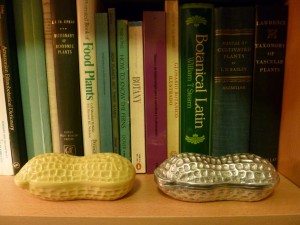

But that’s not all the peanut news for today. Remember the “cute plastic peanut-shaped toys which open to play a jingle“? 1 Well the toy in question finally made it to its intended owner, our very own friend, the genuine Mr Peanut. 2 And he noticed a very strange thing.

Can you spot it? 3

That’s right! The cute plastic Chinese peanut on the left is absolutely identical to the handcrafted Mexican pewter peanut box on the right, down to the last little cell on the surface. And it seems that the pewter version is actually less crisply detailed then the Chinese. So did the Mexican artisan use the Chinese peanut as the form for a mold? Is there some third megapeanut ancestral to them both? Are there other examples of a more-or-less worthless trinket being copied in a more valuable material, rather than the other way round? And is this enough questions for now?

Markets and on farm conservation: it’s complicated

Eating blue tortilla chips during a recent visit to the US reminded me that I had intended to blog about a paper just out in the Journal of Latin American Geography. 4 Entitled “Specialty maize varieties in Mexico: A case study in market-driven agro-biodiversity conservation,” it looks in detail at the economics of growing blue and pozole maize in the areas around the huge market represented by Mexico City. Blue maize is used to make antojitos, savoury meat-, cheese- or vegetable-filled snacks. Pozole is a traditional Mexican maize and meat soup.

The authors, Alder Keleman and Jonathan Hellin, carried out a value chain analysis for both of these distinctive maizes and concluded that “while existing specialty markets clearly provide a strong incentive for farmers to continue to plant blue and pozole maize landraces, this in-and-of-itself … does not provide a complete in situ conservation system.” For one thing, it is not clear to what extent the demands of the market may be driving genetic “standardization” within these specialy types. And in any cases, other types of landraces are not benefiting from these markets, and may indeed be suffering as a result of them.

The authors, Alder Keleman and Jonathan Hellin, carried out a value chain analysis for both of these distinctive maizes and concluded that “while existing specialty markets clearly provide a strong incentive for farmers to continue to plant blue and pozole maize landraces, this in-and-of-itself … does not provide a complete in situ conservation system.” For one thing, it is not clear to what extent the demands of the market may be driving genetic “standardization” within these specialy types. And in any cases, other types of landraces are not benefiting from these markets, and may indeed be suffering as a result of them.

So, although on-farm conservation interventions which involve strengthening these specialty maize value chains, for example through geographical indications, may meet development goals like increasing incomes and food production, they will need to be carefully planned and implemented, and form part of a larger strategy. Which will need to involve genebanks.

Interestingly, another recent paper also looks at the role of markets in on-farm conservation in Mexico (among other things), though for another crop. 5 Kraft and co-workers found that all the landraces of green chile have disappeared in Aguascalientes due to the introduction of hybrids. Farmers still grow landraces for dried chile, in part because of laxer uniformity requirements for dried chile compared to fresh, but are open to the idea of hybrids for this market too. As with specialty maizes, the link between the market and diversity in complicated, and can go both ways. Genebanks are less fun, sure, but at least we know what they do to diversity. Mainly.

Nibbles: Sierra Leone, Cooking traditions, Value chains, Sorghum, Manihot, AnGR

- Sierra Leone gets back to (rural) work.

- Rachel Laudan not keen on UNESCO protecting culinary traditions.

- Value chains are hard.

- Dual-purpose sorghum in the CGIAR spotlight.

- Andy does cassava. Looks like he may need to buy a house in Bellagio.

- Latest Animal Genetic Resources is out. In other news, there’s an international journal called Animal Genetic Resources.

Toma cheese, phone home

“It’s not difficult,” Dr Lombardi said. “What is more difficult is to deliver the product the consumer wants, something not perfect, but with no big flaws either.”

What’s not difficult? To stick an RFID chip and a printed code on the wrapper of a cheese. The code can be read by a smartphone and links the cheese lover “to a phone-optimised website that allows them to browse the information registered about the cheese”.

Matt reports from Terra Madre on a scheme that hopes to add value to Europe’s vast diversity of cheeses and the breeds and ecosystems that produce in a way that even I can understand (and use).