“When countries change their trade policies to protect themselves against price falls, small farmers – particularly those in developing countries – tend to lose profits,” said Will Martin, senior research fellow at IFPRI. “This platform gives governments access to the most recent information available, so they can make informed decisions on food policy that avoid creating global price instability.”

“This platform” is Ag-Incentives, and it’s just been launched by IFPRI.

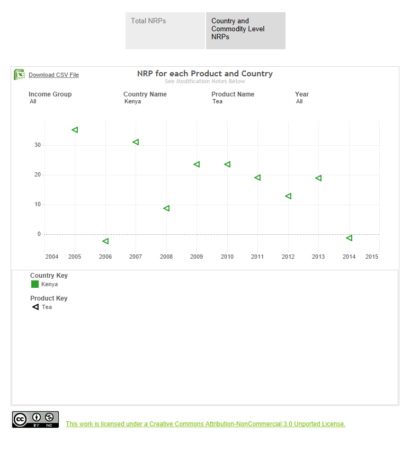

Policies that affect incentives for agricultural production, such as those that raise prices on domestic markets, can artificially distort the global market, which then undermine market opportunities for small farmers in the world. Ag-Incentives allows users to compare indicators, such as nominal rates of protection, across countries and years.

At the moment, it seems that it is only “nominal rates of protection” (NRP) that are being compared, across countries and years, but that will no doubt change as the platform evolves. What are NRPs?

…the price difference, expressed as a percentage, between the farm gate price received by producers and an undistorted reference price at the farm gate level.

The “undistorted price” being “generally taken to be the border price adjusted for transportation and marketing costs.”

If I understand this correctly, if NRP is negative, the commodity is being taxed, positive and it is being subsidised. This is the picture for tea in Kenya, as an example.

I’ll run it by the mother-in-law to see if she can make some sense of it, in particular what happened in 2006 and 2014.