- Informal “Seed” Systems and the Management of Gene Flow in Traditional Agroecosystems: The Case of Cassava in Cauca, Colombia. Farmers move cassava around a lot.

- Ecological and socio-cultural factors influencing in situ conservation of crop diversity by traditional Andean households in Peru. Farmers should be supported in moving tubers around more.

- Nutritional and morphological diversity of breadfruit (Artocarpus, Moraceae): Identification of elite cultivars for food security. There’s a lot of it.

- Man the Fat Hunter: The Demise of Homo erectus and the Emergence of a New Hominin Lineage in the Middle Pleistocene (ca. 400 kyr) Levant. Disappearance of elephant led to replacement of Homo erectus. Quite a difference from the more recent hominin-elephant dynamic.

- Fitness consequences of plants growing with siblings: reconciling kin selection, niche partitioning and competitive ability. All agriculture is about reconciling kin selection.

- Cultivation and domestication had multiple origins: arguments against the core area hypothesis for the origins of agriculture in the Near East. Revisionism rules.

- Tracing genetic differentiation of Chinese Mongolian sheep using microsatellites. Five populations clustered by fancy science into, ahem, five populations.

- Road connectivity, population, and crop production in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fancy science reveals better roads would be good for agriculture. Hell, my mother-in-law could have told them that.

- Econutrition: Preventing Malnutrition with Agrodiversity Interventions. Home gardening is the way to go.

- Carotenoid and retinol composition of South Asian foods commonly consumed in the UK. Palak paneer is not just good, it’s good for you.

Mining the minerals in cowpea

![]() In the wake of recent news of successes in biofortifying root and tuber crops like sweet potato and cassava, it is as well to remind ourselves that grains also provide micronutrients, 1 and a paper in Plant Genetic Resources: Characterization and Utilization does a good job of just that for the somewhat neglected cowpea. 2

In the wake of recent news of successes in biofortifying root and tuber crops like sweet potato and cassava, it is as well to remind ourselves that grains also provide micronutrients, 1 and a paper in Plant Genetic Resources: Characterization and Utilization does a good job of just that for the somewhat neglected cowpea. 2

The authors assessed 1541 accessions from the IITA genebank for the crude protein, Fe, Zn, Ca, Mg, K and P content of the grains. They found fairly wide diversity, but recognized some 9 groups of accessions within which the nutrient profiles were relatively similar. The “best” 50 accessions belonged to only three of these groups, and seven of the best 10 accessions to just one group. While admitting that “increased mineral content in the grains does not guarantee increased nutrient status for the consumer,” they concluded that

…members of some groups such as G5 and G9, which included TVu-2723, TVu-3638 and TVu-2508, would be potential sources of genes for enhancing protein and mineral concentrations in improved cowpea varieties. These lines would therefore be selected and used in crossing for generating segregating populations from where selections can be made for newly developed nutrient-dense cowpea varieties.

It may be the subject of another paper, but what Ousmane Boukar and his co-authors do not do in this one is investigate whether groups G5 and G9, which as I say are based on mineral composition, also hang together morphologically or geographically. Here’s the geographical distribution of the IITA collection, based on data in Genesys (you’ll see it better if you click on it):

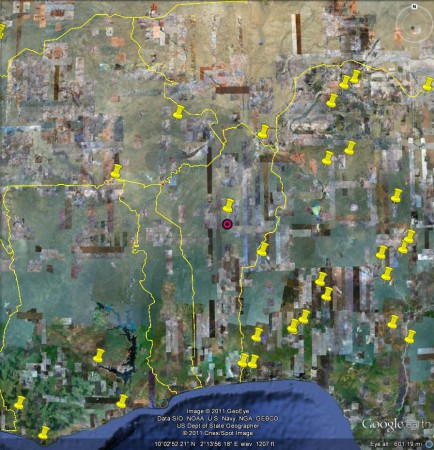

The top 10 accessions in fact come from Benin, India (2), Mali, Nigeria, Puerto Rico, the US (3) and Zaire, so the latter is probably unlikely. Unfortunately, only the Mali and Benin accessions are georeferenced, but look at the nighbourhood of one of them, TVu-8810 from Benin, shown here in red:

Worth collecting a bit more around the village of Borgou?

Nibbles: Law book, Sheep breeding, Pig breeding, Pink mushrooms, Coconut genome, Cassava genome, Apples in the Big Apple, Street food, Irish corner, Peach palm tissue culture, Seed saving, Kenyan farmers, First farmers, Tenure, Peppermint facts, Mountains, Taro network, Shea

- Juliana Santilli guest-blogs on the book Agrobiodiversity and the Law over at Agrobiodiversity Grapevine.

- ICARDA tells communities how to set up a sheep breeding programme.

- While an Indian institute breeds pigs, with Canadian help.

- Another Indian institute does the same for mushrooms, with no help.

- And yet another sequences the coconut genome.

- While BGI sequences a whole bunch of CIAT cassava stuff. Only yesterday they were doing rice. Yeah, but only 50, and you gotta keep those sequencers going, don’t you? Would be nice to know how much the CGIAR is paying BGI annually. Do they get frequent flyer miles? Have they negotiated a corporate rate?

- A Kazakhstan apple tree grows on the East River. A forest, actually. If it had been in England, it might eventually feature here. Ok, ok, our quest for connections is occasionally overdone. Made you look, though.

- Ah, kimchi! Ah, fish empanadas! So much interesting food, only one stomach lining…

- Danny tells us about Ireland’s CWR database. In other news, Ireland has CWR. Oh, and then he goes crazy on the Biodiversity for Nutrition mailing list. Did he get his goat is what I want to know.

- AoB on in vitro peach palms. Why read the paper, when AoB abstracts the abstract?

- Bifurcated Carrots on seed saving in Canada. Video goodness galore.

- And while we’re talking cinema, here’s news of a movie on a year in the life of four Kenyan farmers.

- From Kenyan farmers to First Farmers. The Womb of Nations. I like that. And more. Agricultural hearths. I like that too.

- Four days of discussion about land tenure. May not be enough, actually.

- “…70 per cent of the peppermint sold in the US is descended from a mutant in a neutron-irradiated source.” Good to know.

- I missed International Mountains Day. Again.

- That EU-funded taro mega-project from a PNG perspective.

- What I like about this Worldwatch series on neglected plants is that they’re not factsheets. Yet.

Nibbles: Bees and climate change, Native American seeds and health, Sustainable harvesting and cultivation, Tree death, Grass and C, Vegetables, Fishmeal, Big Milk

Today: Connections Edition, in which we pick low-hanging fruit, think outside the box, and join up the dots.

- The return of a US bumblebee. Is it due to climate change?

- “These foods have meaning” for a Native American tribe (and for Africans for that matter). So will they be able to check out their seeds? And sequence the hell out of them, like rice?

- If you want to harvest palm heart sustainably in the Colombian Andes, only take 10% of any population a year. Is cultivation an option?

- Trees are dying in the Sahel. And yet boffins don’t know how to kill them. No word on what the grass is doing.

- Vegetables and nutrition: the theory and the practice. Of course, a lot of them are grown in cities.

- Why is so much fish made into fishmeal rather than eaten? Location, location, location. Of markets, that is. Kind of like for milk.

Nibbles: Maize and beans, Kenyan stories, Mesopotamia, Rice Domestication, Food economics, Pest control

- The climate change boys have been looking for places where maize and beans will, and will not, thrive.

- An Australian journalist reports from Kenya, courtesy of The Crawford Fund.

- Rewriting the metanarrative of The Fertile Crescent.

- Dorian Fuller goes on to examine recent papers on rice and millet domestication … so we don’t have to.

- Back40 previews Tyler Cowan’s new book An Economist Gets Lunch: New Rules for Everyday Foodies. Can I wait until April?

- How to control stemborers and striga with agrobiodiversity. Undated. Is it new?

- Arche Noah revitalized? Again, is this new? C’mon people, date those suckers.