- Conserving dambos for livelihoods in southern Africa. How many CWRs are found in such wetland habitats around the world, I wonder.

- Cucumis not out of Africa.

- Exploring “the connection between traditional knowledge of herbs, edible and medicinal plants and media networked culture.” And why not.

- PBS video on malnutrition.

- Fungal exhibition at RBG Edinburgh.

- Indian Council on Agricultural Research framing guidelines for private-public partnerships in seed sector. That’ll stop the GM seed pirates.

- Conserve African humpless cattle! They’re needed for breeding.

- UG99 — and crop wild relatives — in the news. The proper news. The one people pay attention to.

- Vanilla lovers better start stocking up.

- Kenyan farmers earning money selling sorghum to brewers. What’s not to like.

Conserving crop wild relatives in situ is hard

Our friends at Bioversity International have a nice piece on IUCN’s website summarizing their work on in situ conservation of crop wild relatives with over 60 partners in five countries around the world. I liked the general tone of understatement: “What became obvious from the project’s outset was that the in situ conservation of CWR is not an easy task and cannot be achieved alone.” The practical lessons of the project have been brought together in a manual.

The piece also includes a trenchant quote from a recent IUCN publication: ((Amend T., Brown J., Kothari A., Phillips A. and Stolton S. (eds.) 2008. Protected Landscapes and Agrobiodiversity Values. Volume 1 in the series, Protected Landscapes and Seascapes, IUCN & GTZ. Kasparek Verlag, Heidelberg.))

In general, the idea that the conservation of agrobiodiversity is a potentially valuable function of a protected area is as yet little recognised. For example, it would appear from the case studies that it hardly ever appears explicitly in protected area legislation, and rarely in management plans. Indeed, a study by WWF found that the degree of protection in places with the highest levels of crop genetic diversity is significantly lower than the global average; and even where protected areas did overlap with areas important for crop genetic diversity (i.e. landraces and crop wild relatives), little attention was given to these values in the management of the area (Stolton et al 2006).

The horse in Mongolian culture

They may be trying to develop and diversify their agriculture now (well, since the 1950s), but Mongolians are traditionally very much a nomadic herding culture, with the horse at its centre. ((Though that doesn’t stop them growing small patches of wheat around their temporary encampments, out west in the Altai Mountains.)) One expression of that is how early kids learn to ride.

They may be trying to develop and diversify their agriculture now (well, since the 1950s), but Mongolians are traditionally very much a nomadic herding culture, with the horse at its centre. ((Though that doesn’t stop them growing small patches of wheat around their temporary encampments, out west in the Altai Mountains.)) One expression of that is how early kids learn to ride.

Most young Mongolians — boys in particular — learn to ride from a very young age. They will then help their fathers with the herding of goats, sheep and horses. Some children have a chance to ride at festivals called Naadam — the biggest of which is held on 11th-13th July in Ulaanbaatar — though there are naadams held throughout the year all over the countryside. Young jockeys between the age of 5 and 12 (girls and boys) race horses over distances ranging from 15km to 30km. There are 6 categories for the races depending on the horses’ age, including a category for 1 year old horses (daag) and one for stallions (azarag).

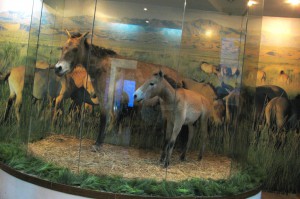

Alas, this museum display is as close as I got to seeing the famous Mongolian Wild Horse or Przewalski’s Horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), locally known as takhi.

It’s possibly the “closest living wild relative of the domesticated horse, Equus caballus.” Certainly it is genetically very close to the local domesticated breed based on molecular markers, though that could be because of interbreeding. Last seen in the wild in 1969, its restoration in China and Mongolia from captive stock, for example to the Hustain Nuruu National Conservation Park, is one of the great conservation success stories.

Sea buckthorn becoming a success in a land with no sea

The name of the game in Mongolian agriculture is diversification. And one of the things researchers at PSARTI, the Plant Science Research and Training Institute in Darkhan, and others are looking at is a shrubby berry called sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) with some interesting nutritional properties. They have put together a small germplasm collection of local and introduced material and are doing agronomic trials of various kinds, trying to find the best varieties for different purposes. In fact, the plant has a pretty long and rich history in Mongolia:

It is said that Genghis Khan, the Mongol conqueror, who established one of the largest empires from China to Eastern Europe in the 13th century, relied on three treasures: well organized armies, strict discipline and Seabuckthorn. Seabuckthorn berries and seed oil made Genghis Khan’s soldiers stronger than his enemies.

There are already some products on the market. Like this delicious icecream, called Ice Doctor.

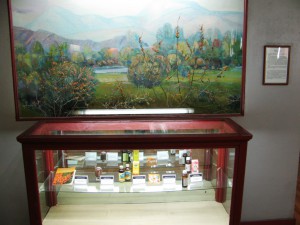

The natural history museum in downtown Ulaanbaatar has a display featuring a number of locally-made products — a couple of different oils and “globules” — along with a somewhat threadbare diorama.

I guess commercialization still has some way to go, but a start has been made. Another wild species with some commercial potential may be strawberries.

Wild Allium of various kinds is also sold in the market.

Unbottling the lentil

![]() It is well known that crops go through a genetic bottleneck at domestication. Due to the founder effect, they typically show a fraction of the genetic diversity found in their wild relatives. Which is bad, but fixable: fixing it is the plant breeder’s job — or part of it anyway. What’s less well known, according to a recent paper on lentils by Willy Erskine and co-authors in GRACE, is that the movement of a crop around the world can also often lead to bottlenecks. ((Erskine, W., Sarker, A., & Ashraf, M. (2010). Reconstructing an ancient bottleneck of the movement of the lentil (Lens culinaris ssp. culinaris) into South Asia Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution DOI: 10.1007/s10722-010-9582-4))

It is well known that crops go through a genetic bottleneck at domestication. Due to the founder effect, they typically show a fraction of the genetic diversity found in their wild relatives. Which is bad, but fixable: fixing it is the plant breeder’s job — or part of it anyway. What’s less well known, according to a recent paper on lentils by Willy Erskine and co-authors in GRACE, is that the movement of a crop around the world can also often lead to bottlenecks. ((Erskine, W., Sarker, A., & Ashraf, M. (2010). Reconstructing an ancient bottleneck of the movement of the lentil (Lens culinaris ssp. culinaris) into South Asia Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution DOI: 10.1007/s10722-010-9582-4))

Lentil cultivation moved from Afghanistan into the Indo-Gangetic Plain sometime between 7000 and 4000 BC. The authors “reconstructed” this movement by growing random subsets of the ICARDA world lentil collection at two sites, Islamabad and Faisalabad, in Pakistan. Faisalabad is typical of conditions in the Plain, Islamabad is a transitional, mid-altitude environment.

They found that most Afghani accessions did not flower in Islamabad before the local material matured, due to a combination of temperature and photoperiod, the main determinants of flowering in lentils. The few that did were among the most late-flowering in the world. This is probably related to the shift in sowing from winter to spring as lentils moved from their area of origin in lowland SE Turkey and N Syria into the central Asian plateau. The data from Faisalabad in addition showed that every week’s delay in flowering resulted in a 9% loss of yield potential in the lowlands.

So there was strong selection for reduced sensitivity to photoperiod and a return to early flowering as the lentil moved into the Indo-Gangetic Plain, and consequently a genetic bottleneck. ((Incidentally, I am told by Jacob that a genetic bottleneck related to flowering time (earliness) also occurs in the Northern flint maize varieties in the US and Canada.)) But in a way the surprising thing is that there was no cork in the bottle. Where did the genetic variation that allowed adaptation to the Plain come from? The authors note that time to flower in lentils is controlled by both single gene and polygenic systems, and that early flowering is always recessive. Those recessive alleles for early flowering, which may have come from introgression from a wild relative in Afghanistan, must have occasionally come together and been selected for at mid-altitudes, which then “allowed selection for a radically earlier flowering habit as a new adaptive peak for the novel environment of the Indo-Gangetic Plain.”

The challenge is now for breeders to use these insights to broaden the genetic base of the crop in India, where lentil germplasm “is among the least variable among lentil-producing countries for agro-morphological traits … despite its vast area of cultivation there today.”