A massive EU study looked into the DNA of 487 different kinds of wheat, including wild relatives, close domesticated cousins, old landraces, old cultivars and modern elite varieties. All bread wheat falls into one of three separate clusters. There is a founder population that represents primitive landraces originating in the Fertile Crescent and modern varieties that came about as part of the green revolution. It includes older varieties from Western Europe. A separate cluster contains varieties from Eastern European countries, developed after about 1955 during the cold war. The third cluster contains mostly varieties developed after about 1985 that mix DNA from the founder population and the Warsaw Pact cluster, reflecting a greater exchange among breeders after 1989.

There’s more, especially for wheat nerds such as myself.

The nerd in question is Jeremy, and his further thoughts are on his newsletter. I have his permission to reproduce the piece in full here, but I suggest you subscribe to the newsletter, it’s always full of interesting food-related stuff.

For one, Asian and European cultivars are much less similar than one might expect. Farmers in the two regions, while pursuing the same overall goal of greater productivity, seem to have done so by selecting different genetic targets for their work. Breeders now have more specific information about the stretches of DNA that they might want to target as they go about creating new varieties that can cope with changing climates.

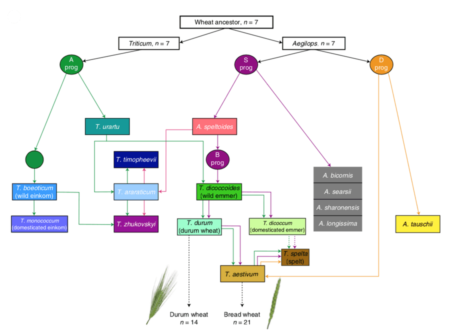

Overall, the current picture of the evolution of wheat remains the same – complex – albeit with stronger support for some of the putative pathways. Personally, that’s a great relief. It means I don’t have to scrap any of the episodes of Our Daily Bread devoted to the evolution of wheat.

The original research paper Tracing the ancestry of modern bread wheats is behind a paywall, a scandal for taxpayer-funded research, but that’s another story. I suspect that anyone who needs more detail will have access, but if you just want more details, drop me a note.

You can also leave a comment below.