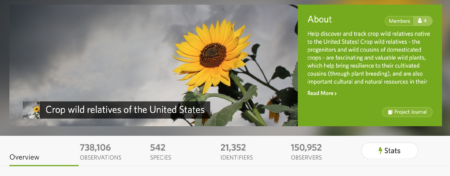

Our friend and occasional contributor Colin Khoury has made a “project” on iNaturalist focusing on the crop wild relatives found in the USA.

iNaturalist collates and manages citizen science observations of living things, with a machine learning algorithm helping with species identification. If the observation you document on your phone app gets verified by two other people, it’s rated as “Research Grade,” and included in GBIF.

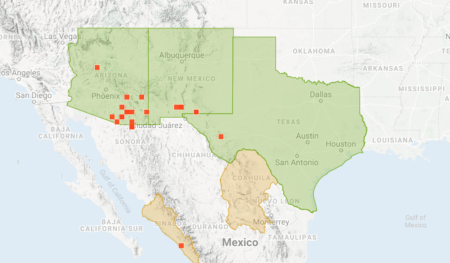

Colin also had a go at pulling together observations on major food crops, though there’s no way of including only observations of cultivated material. This is a map of tepary beans (Phaseolus acutifolius), for example.

Cool, no? Join in! There’s only one observation of Bambara groundnut. Surely we can do something about that.