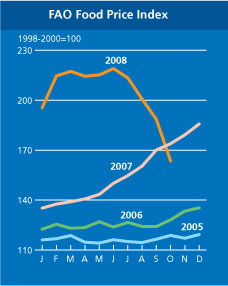

You’ll remember that I recently bewailed the lack of studies documenting and promoting the use of agrobiodiversity in coping with HIV. But Peace Nganwa, an intern at the African Centre for Food Security, University of KwaZulu-Natal, must have access to some relevant data on this because she suggests that recent food price increases have resulted in reduced dietary diversity, among other things:

In the face of these price hikes, households and communities have to adopt coping strategies to enable them to survive. Some of these coping strategies include: change in diet such as reduced food intake, lower food quality and reduced dietary diversity; seeking wage employment; temporary or in the worst case permanent migration; sale of productive and non-productive assets; and withdrawal of children from school.

In a very cogent article at AllAfrica.com she describes why good nutrition is particularly important to those living with HIV.

Firstly the infection-illness period, which on average is about eight years, can be extended by a good diet, among other things. People infected by the virus have up to 50 per cent more energy requirements (100 per cent for children) than people who are not infected. Secondly good nutrition both in quality and quantity is vital in the prevention of opportunistic infections which occur because of reduced body immunity. A sound diet may therefore prolong life; more especially delay the progression of HIV to AIDS. Thirdly adequate nutrition is of utmost importance to the patients on anti-retroviral therapy. Some drugs must be taken with food and most are not effective if the patients are malnourished.

I just don’t get why there seem to be so few studies and interventions out there trying to help PLWHA by promoting diverse crops for diverse diets, especially in urban settings. Tell me I’m wrong. Please.