In case anyone out there is still wondering why all those early promises of drought-resistant crop varieties have been so long arriving, Ford Denison has a wonderfully clear explanation. He takes as his starting point a 2004 paper about the development of Drysdale wheat, bred in Australia for water use efficiency. And he came to that in search of counterexamples to his default view.

I’m always skeptical when someone speculates that we could double crop yield just by increasing the expression of some newly discovered “drought-resistance gene.” My rationale is that mutants with greater expression of any given gene are simple enough to have arisen repeatedly over the course of evolution.

The question Denison asks of Drysdale wheat is whether the tradeoffs that in the past prevented the selection of greater productivity — for example the ability to withstand drought being penalized in average and wetter years — are no longer relevant.

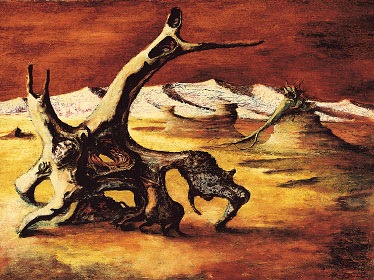

Rather than give away the answer, or attempt to summarize the key arguments, I just urge you to go and read the full post. I will, however, add a little tidbit I discovered all on my own (with Google’s help). You might think that naming a drought-resistant wheat Drysdale marks a marketing triumph. You would be wrong. It recalls Russell Drysdale, an Australian artist whose paintings of rural life in general and drought in particular captured the land and its people.