Last week saw the publication of a couple of papers about early agriculture in two very different regions which will probably have people talking for quite a while. From Snir et al. 1 came a study of pre-Neolithic cultivation in the Near East. And from the other side of the world, there was the latest in the controversy over the extent of Amazonian agriculture from Clement et al. 2.

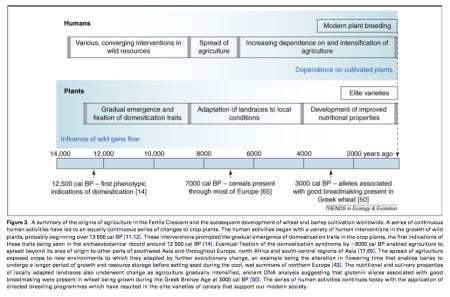

Yes, I did say pre-Neolithic. The key finding of the archaeological work described by the first paper is that 23,000 years ago, or over 11 millennia before the putative start of agriculture in the Fertile Crescent, hunter-gatherers along the Sea of Galilee in what is now Israel maintained little — and, crucially, weedy — fields of cereals. The archaeobotanists found remains of both the weeds and the cereals at a site called Ohalo II, as well as of sickles, and the cereals were not entirely “wild”, as the key domestication indicator of a non-brittle rachis was much more common than it should have been. To see what this means, have a look at this diagram from a fairly recent paper on agricultural origins in the region. 3

Those “first phenotypic indications of domestication”, dated at 12,500 years ago, need to be pushed quite a bit leftwards on that timeline now, off the edge in fact. A non-shattering rachis, it seems, was quite a quick trick for wild grasses to learn. But the process by which they acquired all the other traits that made them “domesticated” was very protracted and stop-start.

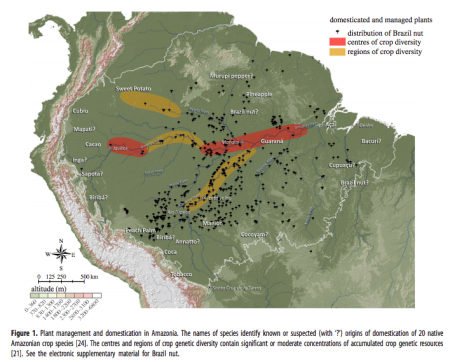

Zoom over to Amazonia, and the transition to farming took place much later, probably around 4,000 years ago, according to the other paper published last week. But it was just as significant as in the much better-known “cradle of agriculture” in the Fertile Crescent, with perhaps 80 species showing evidence of some domestication. The difference, of course, is that Amazonian agriculture was based on trees, rather than annual grasses and legumes.

According to the authors, parts of the Amazon basin, in particular those now showing evidence of earthworks and dark, anthropogenic soils, were just as much managed landscapes by the time of European contact as the places those Europeans came from. But compare our collections of crop diversity from the Amazon basin (courtesy of Genesys, which admittedly does not yet include Brazilian genebanks)…

with what we have from the Near East…

If we want to know more about how the domestication process and transition to agriculture differed in the Amazon and the Fertile Crescent, there’s a whole lot of exploration still to do.

- Snir A, Nadel D, Groman-Yaroslavski I, Melamed Y, Sternberg M, Bar-Yosef O, et al. (2015) The Origin of Cultivation and Proto-Weeds, Long Before Neolithic Farming. PLoS ONE 10(7): e0131422. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131422

- Clement CR, Denevan WM, Heckenberger MJ, Junqueira AB, Neves EG, Teixeira WG, Woods WI. 2015 The domestication of Amazonia before European conquest. Proc. R. Soc. B 282: 20150813. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.0813

- Brown, Terence A., Jones, Martin K., Powell, Wayne and Allaby, Robin G.. (2008) The complex origins of domesticated crops in the Fertile Crescent. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, Vol.24 (No.2). pp. 103-109. ISSN 0169-5347