28 July 2011 marks the first anniversary of the 2010 floods in Pakistan — one of the world’s most devastating natural disasters in recent times. Nearly a fifth of the country was flooded, affecting over 20 million people and resulting in some 14 million people in need of humanitarian aid. Livestock was killed, crops were destroyed, and infrastructure and other livelihood assets were damaged on an unprecedented scale.

Dirk Enneking posted a link to the article from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs from which this quote is taken on his Facebook page earlier today, with this comment:

…let’s hope that grasspea consumption is not excessive. It saves lives but for some it is at the cost of lifelong crippling. Hence its use as a food needs to be managed carefully.

I wondered why grasspea consumption might be expected to be excessive after floods, and Dirk was kind enough to explain:

…since it is cultivated there, it grows after floods when other crops don’t and some people have nothing else to eat; and it is cheaply available from across the border in India — classic situation for a lathyrism epidemic…

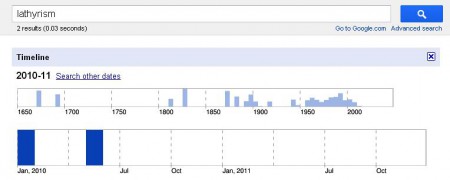

Interesting, I thought. So is there any evidence of a lathyrism epidemic in Pakistan in the aftermath of the flooding. Google Trends picks up the blip in searches for “Pakistan floods” in 2010, of course, but there are no subsequent blips for “lathyrism” or indeed “epidemic”.

And there’s also no evidence from Google of increased references to lathyrism in news items after the 2010 floods.

Not yet, anyway. Something to keep an eye on…

The idea to check google for a correlation between lathyrism (or more precisely neurolathyrism) and floods is a good one, however, when the literature is scrutinised, there is actually very little that can be found on lathyrism following floods. Despite the paucity of documented evidence on the association of lathyrism with floods, many documents repeat the mantra that grasspea survives droughts and floods better than other crops, hence the nice correlation in google.

I found only very few reports during research for my recent paper [Enneking, D. (2011) The nutritive value of grasspea (Lathyrus sativus) and allied species, their toxicity to animals and the role of malnutrition in neurolathyrism. Food and Chemical Toxicology 49:694–709].

The villagers subsisted on it for 3 to 4 months each year for a period of 6 years. [Chaudhuri, R. N.; Chhetri, M. K.; Saha, T. K., and Mitra, P. P. (1963) Lathyrism: a clinical and epidemiological study. J Indian Med Assoc. 41:169-73.]

In 1989, Kaul reported that his team collected grasspea (Lathyrus sativus) “types that would remain viable under several feet of flood water during the monsoons.” [Kaul, A. K. (1989) Future strategy for the collection, characterization, storage and utilization of Lathyrus. pp. 188-190. In: Spencer, P. S. and Fenton, M. B., Eds. The Grass Pea: Threat and Promise. Proceedings of the International Network for the Improvement of Lathyrus sativus and the Eradication of Lathyrism. Third World Medical Foundation, NY.]

There is considerable trade of the crop in India, including states bordering on Pakistan [Dixit, S.; Khanna, S. K., and Das, M. (2008) Non-uniform implementation of ban on Lathyrus cultivation in Indian states leading to unwarranted exposure of customers. Current Science 94:570-572].

This constitutes a potential cheap food and seed supply for people affected by the floods.

The following is extracted from Haqqani et al. (2000):

Considering that Upper Sindh province in Pakistan produces the bulk of Pakistan’s grasspea crop and that significant parts of this cultivation area were flooded while the local population is severely impoverished by loss of assets, this looks like a classic situation for the development of lathyrism in isolated villages or families.

Harvest of the crop would have commenced in April. It takes 1-3 months of exclusive grasspea consumption for neurolathyrism to develop.

With all the aid pouring into the country and teams monitoring the food situation, it would be good to see some attention being given to this issue by including the crop in surveys of markets and villages.

Strategies for prevention include leaching of the seed toxins or dilution of the diet with cereals.