Joseph Needham is known as the Man Who Put the S in Unesco. And he did indeed successfully lobby Julian Huxley for the inclusion of science in the mandate of that new-fangled UN organization. More importantly, however, he is also known for his monumental work Science and Civilization in China. Eventually stretching over 27 volumes and comprising more than three million words, Needham worked on the project for the best part of fifty years, from the Caius College, Cambridge room which is now inhabited by Stephen Hawking, as it happens. And the volumes have continued coming out after Needham’s death in 1995.

Joseph Needham is known as the Man Who Put the S in Unesco. And he did indeed successfully lobby Julian Huxley for the inclusion of science in the mandate of that new-fangled UN organization. More importantly, however, he is also known for his monumental work Science and Civilization in China. Eventually stretching over 27 volumes and comprising more than three million words, Needham worked on the project for the best part of fifty years, from the Caius College, Cambridge room which is now inhabited by Stephen Hawking, as it happens. And the volumes have continued coming out after Needham’s death in 1995.

But what possessed him to set off on such a journey, a journey which would consume his whole life? Well, it’s a fascinating story, and beautifully recounted by Simon Winchester, who wrote a recent biography of Needham, in a podcast in TVO’s Big Ideas series. If you’ve got an hour spare, listen to the whole thing. If you don’t, skip to 38 minutes in, and just listen to Winchester’s description of the epiphany Needham had in 1942 in a Kunming garden, a matter of only hours into his first visit to China, after five years of obsessively studying the language back in Cambridge at the knee 1 of his remarkable Chinese biochemist mistress. Needham had an interesting, complicated private life. Anyway, he was there on a mission from the British government to report on the needs of Chinese universities during the difficult years of the Japanese occupation, when they had in effect migrated west, trying desperately to continue functioning under siege.

That epiphany has to do with agricultural biodiversity, and is the reason why I’m talking about this here. Although of course Needham’s work includes huge accounts of botany, agriculture and agroindustries, forestry, cooking and food sciences, and one of these days I’ll have to delve into them to see what they say about numbers of varieties in the past. But one thing at a time, what Needham saw in that wartime garden was an…

That epiphany has to do with agricultural biodiversity, and is the reason why I’m talking about this here. Although of course Needham’s work includes huge accounts of botany, agriculture and agroindustries, forestry, cooking and food sciences, and one of these days I’ll have to delve into them to see what they say about numbers of varieties in the past. But one thing at a time, what Needham saw in that wartime garden was an…

…old Chinese gardener in ragged blue coat and trousers with a wispy white beard who potters around smoking one of these long pipes with a tiny bowl — and a mongol cap, periodically performing elaborate grafting techniques on the plum tree. 2

Comparing that technique to what he remembered his father doing in their London SW11 garden many years before brought home to him how differently they did things in China. But there was something else. Here’s Winchester:

Perhaps the Chinese not only did their grafting differently but may have done this different kind of grafting very much earlier than anyone in Europe had done anything like it. Perhaps this old man’s technique was thousands of years old. Further still, quite possibly Needham could prove it was thousands of years old by researching old Chinese books on botany — which of course he could now read with ease.

He did research the problem of course — for fifty years. And it’s true, he did prove the antiquity of the grafting techniques that he saw. And of many other Chinese inventions too, thousands of them. That was the project of Science and Civilization in China. It changed the West’s perception of the Middle Kingdom forever, and the idea of it was born watching an old man top graft a plum tree in a Kunming garden.

There’s a coda to the story. The ashes of Joseph Needham and his two wives (both interesting characters in their own right), whom he outlived, were commingled on his death and spread under a Chinese plum tree growing in the gardens of the institute named after him in Cambridge, and which continues his work.

- As it were.

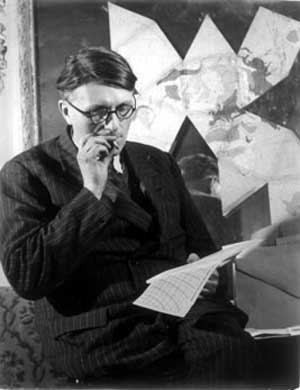

- The photo is from autan’s Flickr stream, used with thanks under a Creative Commons license.