Kirinyaga County government will this week start distributing free Gadam sorghum seeds to residents of South Ngariama settlement scheme as way of fighting poverty in the area. The exercise which will see the residents receive 2,000 kg of the free seeds is expected to be flagged off by Governor Joseph Ndathi.

Interesting enough, but a month-old Kenya News Agency press release about the distribution of some sorghum seed, even free sorghum seed, wouldn’t normally exercise me unduly. Except, that is, when the above is followed by this:

The Gadam sorghum is best suited for industrial production of beer and farmers are expected to rake thousands of shillings from sale of the produce which will be marketed to the Kenya Breweries Limited (KBL).

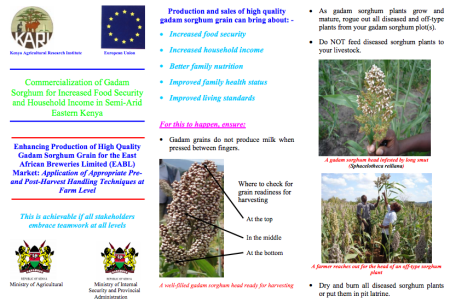

Ah, well, now you’re talking. I did know that sorghum is increasingly being used in beer brewing in Kenya, but I didn’t realise that there was a specific variety involved, I thought any old sorghum, including landraces, would do. You can get extension leaflets on Gaudam, such as this:

Which is just as well, because there are clearly some problems with it, as well as undoubted advantages, in particular earliness. The value chain for sorghum beer in Kenya has been well documented, and from that study comes this admittedly sketchy description of the Gadam variety and its history:

Sorghum beer is made from Gadam, a semi-dwarf sorghum variety with specific market traits, including white colour, low tannin and a high starch content. Originating in Sudan, Gadam was officially introduced in Kenya as a food crop in 1972 but then re-launched as an industrial crop in eastern Kenya in 2004. The KARI Seed Unit, located at Katumani, was established to grow and market seed of open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) that were unprofitable for private seed companies. It is the biggest producer of sorghum seed in Kenya. The Seed Unit sub-contracts seed production to 3000 growers who are advanced seed and repay in kind after harvest. The minimum acreage for a contract farmer is five acres. The Seed Unit buys whatever quantity farmers want to sell, provided it passes seed inspection by KEPHIS. Sales are made to large buyers but not to stockists because of risk of adulteration

Gadam is widespread and common enough to have been included as a sort of control in a recent survey of sorghum diversity in Kenya, which includes this passage:

In contrast to the case of some landraces, improved varieties were uniformly distributed and their frequencies did not differ between ethnic groups. The recently introduced Gadam variety was genetically distinct from the landraces and showed limited introgression from the other genetic clusters. It was genetically uniform and complied with certified control. However, farmers also gave the names of local and already known variety to individuals that have the same genetic profile as Gadam, an improved variety. This can be explained by a morphological similarity. Yet it raises the question of the consequences this will have for the on-farm evolution of the improved variety. Kaguru, for instance, which was introduced in the area 10–15 years ago, seems to have evolved differently across ethnic groups.

So Gadam‘s genetic future is uncertain. It may well change significantly, and in different ways in different places, and that will be interesting to follow, though those brewers may perhaps object. But what about its past? Can we trace Gadam back in time to its source? Unfortunately, I was not able to find anything online about its pedigree or breeding history, beyond hints at the involvement of ICRISAT, and vague references to an ultimate origin in Sudan. I’ll have to ask some sorghum experts, I suppose. Or look harder. However, my searches did produce one lead. There are 5 entries in GRIN that feature the word Gadam, including two from Sudan, a 1945 introduction called Gadam El Haman, PI152664, and a much later introduction called Gadam El Hamam, PI571389.

Note the slight difference in the last word of the name — hamaN versus hamaM. I think the first version may perhaps be a typo. I can’t find an Arabic word that can plausibly be transliterated as hamaN; hamaM, on the other hand, may mean “bath,” or perhaps “dove.” Gadam is even trickier, because that initial G could equally be a ق (leading to the noun “foot”, or possibly to a verb which may mean “to present”), or a خ (leading to the verb “to serve”). Bringing my mighty Arabic resources to bear on the problem, I conclude that the full name could well be translated as “footbath.” Or perhaps “serving the dove.” The perils of a little knowledge. Whichever it is (and I can’t for the life of me think why a sorghum variety should be called either), I’m no closer to knowing whether either, or neither, of those PI numbers is the ultimate source of Kenya’s Gadam, tout court. But I’m going there next week. Maybe I’ll ask around. If I find anything, I’ll let you know. And have a sorghum beer in celebration.

Suggest for me the supplier of this seed(Sorghum gadam) in Uganda am interested in it