Our friend Dr Ola Westengen just sent us this post on a paper that he’s just had published. Keep it up, Ola, and thanks.

In a new study published in PNAS this week we stand on the shoulders of Jack R. Harlan et al. and take a molecular approach to test some interesting hypotheses on the factors shaping diversity in sorghum. In the book Origins of African Plant Domestication, from 1976, Harlan and Stemler summarized findings from their Crop Evolution Laboratory at Illinois University and proposed that the five basic “races” of sorghum identified were associated with language distribution in Africa: “Guinea is a sorghum of the Niger-Congo family, kafir a Bantu sorghum. Durra follows the Afro-Asian family fairly closely, and caudatum seems to be associated with the Chari-Nile family of languages” (p. 476). This kind of crop-language co-distribution would be in support of the contested farming-language co-dispersal hypothesis (by Diamond and Bellwood). Genetic studies have hitherto not directly explored the molecular support for this sorghum-language co-distribution hypothesis — maybe because such studies have found “little correspondence between races and marker-based groups” (Billot et al.).

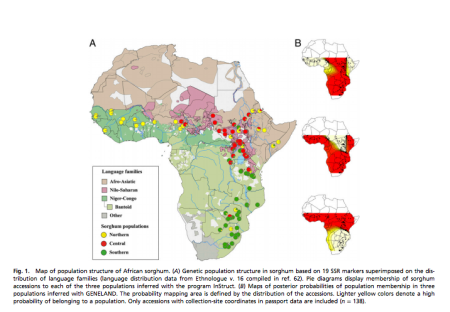

We let go of the race concept and based on molecular markers we modelled the population structure in a panel of 200 ICRISAT accessions with a broad geographic origin. We identified a pattern that is in strong support of the notion that sorghum diversity and ethnolinguistic groups are associated in Africa. We identified three major sorghum populations: a Central population co-distributed with the Nilo-Saharan language family; a Southern population co-distributed with the Bantu languages; and a Northern population distributed across northern Niger-Congo and Afro-Asiatic language family areas.

A case study of the seed system of the Pari people, a group descending from the proposed first Nilo-Saharan sorghum cultivators, living in today’s South Sudan, provides a window into the social and cultural factors involved in generating and maintaining the pattern seen at the continental scale. We show that the age-grade system, a cultural institution important for the expansive success of this group in the past, governs the traditional sorghum seed system in a way that maintains the Pari sorghum landraces as a metapopulation. Thus, we can make Harlan and Stemler’s words as ours: “It has been our observation that the races of sorghum are intimately associated with the cultivators who grow them.”

So Harlan et al. are our main references, but how did we start thinking along these ethnolinguistic lines in the first place? Well, like many others in the community we regularly read this excellent blog.