The low level of activity last week on the blog was due to the fact that I was at the Botanic Garden Meise in Belgium participating in the annual meeting organized by the Genebank Platform. You can get a flavour of what happened from Twitter. And yes, I’m sorry, I should have told you all about #genebanks2017 before the meeting, rather than after. My bad.

Anyway, we’re finalizing the Platform’s website and you’ll be able to read all about it there soon. In the meantime, you can see a nice pic of the genebank managers and others working in some of the world’s largest and most used genebanks on the Crop Trust’s Facebook page.

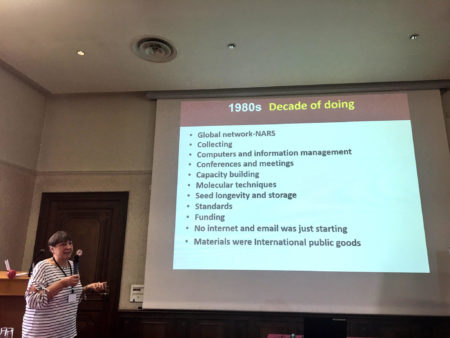

One of those managers is Jean Hanson, and she’ll be retiring from her job at ILRI at the end of the year. In her farewell presentation to the group she summarized the history of plant genetic resources conservation, from the point of view of the international collections, in this way:

- 1970s: The Decade of Getting Started

- 1980s: The Decade of Doing

- 1990s: The Decade of Uncertainty

- 2000s: The Decade Upgrading

- 2010s: The Decade of Accounting

Jean didn’t say in her talk what she thought the 2020s were going to be the decade of, but she did share some thoughts during the Q&A. So let me open it up. What do you think? What do the 2020s have in store for the conservation of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture?

The 2020s will be the Decade of the Farmer. Participatory breeding and variety selection will take a high flight. Farmers will organize themselves to lead innovation. Breeders and genebanks will become service providers to strong farmer research networks, who will be demanding a high level of professionalism.

With farmers’ support, genebanks will have a clear political platform and receive a steady stream of public and private investment.

Or is this the 2030s?

Very scientific evaluation more than characterization. It will give options og good accessions to be cleaned trough biotech and return them to farmers field with two purposes. 1. To increase food production and also to demostrate thebusefulness of quality seed. Genomic work in the main crops of poor farmers will not be delivering before 2020. Im doing it with yam in Ghanak

One example. Pona yam in Ghana is a group of clones derived from a monoecious/dioecious genotype. Farmers and traders knows it cery well. Gen banks probably have one or two of the group so they are not representing the diversity in the field. Defining a true to type basic groups of this case, cleaning them effectivelly and registering them to send them back to increase productivity is another case of this crop applicable to all root and tuber crops. In Guyana, the variety to produce yellow Gari Is a composite of 20 clones which farmers plant in a determined number of cuttings per clone to get the good quality. So Gen Banks should keep it to analyze genetic diversity and deliver for breedding.

I hope it will be a return to the “Decade of Doing”–accounting really sucks… I also hope it will be the “Decade of Farmers,” as Jacob wrote…we have some great resources in our collections, and it’s time to plant them back where they came from or into environments that are similar to their origins, and see what happens!

The 1990s and 2000s were also ‘Decades of Doing’ at IRRI. We completely refurbished and revamped our conservation infrastructure, enhanced conservation protocols (incl. seed physiology and seed regeneration research), increased the size of the collection by 25% through a concerted collecting program in partnership with many countries in Asia, Africa and Costa Rica, and began work in the mid-90s on the application of molecular markers in a genebank collection. Yes, we had the ‘accounting’ but that didn’t stop us from getting on with the necessary and exciting aspects of germplasm conservation.

But moving forward, it has to be the ‘Decades’ of genomics, to really dissect the diversity (particularly useful diversity) in these important collections.