Jeff Horwich has an interesting post over at HarvestChoice Labs looking at the effect of the tsunami on agriculture in northern Japan. He used the Droppr tool, which combines Google Maps with lots of other data, in this particular case the world-wide crop distribution data from the Spatial Production Allocation Model (SPAM). In SPAM

…tabular crop production statistics are blended judiciously with an array of other secondary data to assess the production of specific crops within individual ‘pixels’ – typically 25–100 square kilometers in size. The information utilized includes crop production statistics, farming system characteristics, satellite-derived land cover data, biophysical crop suitability assessments, and population density.

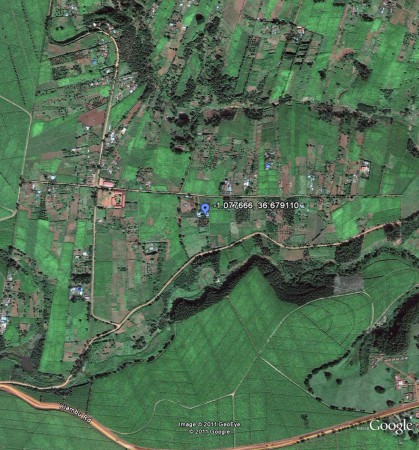

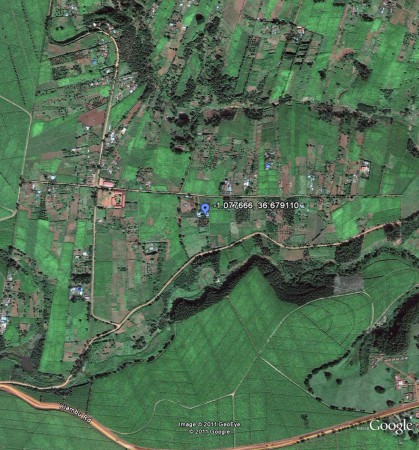

Intrigued, I decided to do a little lighthearted ground-truthing of the SPAM data. I only looked at one location, I admit, but what I found was a bit disappointing. I zoomed in on the location of the mother-in-law’s farm in the Limuru highlands (-1° 4′ 39.60″, +36° 40′ 44.80″). Here’s what the place looks like.

This is the view from space, courtesy of Google Earth.

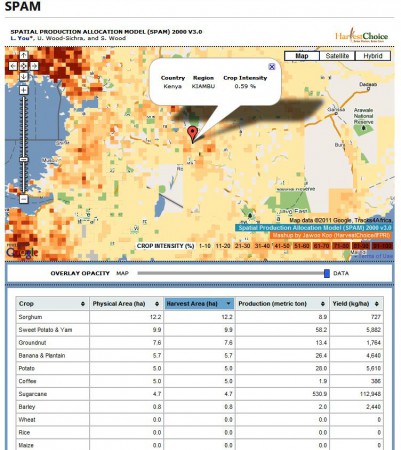

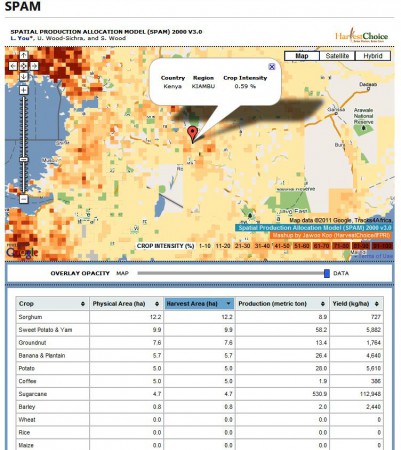

Now, according to the SPAM methodology that’s a cropping intensity of 0.59%, with the main crops being sorghum, sweet potato/yam, groundnut, banana/plantain, potato, coffee and sugarcane.

Jeff very niftily embedded both a map and a spreadsheet of the production data for the main crops in his post, but I wasn’t able to work out how to do that. So you’ll have to make do with this wholly inadequate screengrab, I’m afraid.

What my mother-in-law and her neighbours actually grow is maize, beans, potato and tea, tea and tea. A pretty different set of agrobiodiversity to what SPAM thinks. And I think she would be surprised at the low value of cropping intensity. This is a very high-potential area.

Anyway, that’s only one data point. It would be interesting to know from the SPAM guys if there’s a more systematic attempt going on to check on, and refine, the results of the model.

AgriCultures Network has a couple more modules in its

AgriCultures Network has a couple more modules in its