- Executive Director of CBD perpetuates myth that we have lost 75% of crop diversity, at high-level meeting, no less.

- 670 agroforestry trees in a database, courtesy of ICRAF.

- Last Rice Today of this year, the 50th anniversary of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), summarized.

- Soil community helps maintain species and genetic diversity.

- Good news for some UK bumblebees.

- On the agricultural frontier in South America. Any crop wild relatives there?

- Global Network of National Geoparks expands. Any crop wild relatives there?

The dismal science and dismal science writing

I was a bit flippant a few days ago about the costs of genebanks. And I felt guilty enough about it, especially after Jeremy’s recent piece at Vaviblog on the value of germplasm collections, to look into it a bit more.

It all started with an article in IITA’s R4D Review which looked at the costs of conserving the cowpea collection there. The bit I had trouble with was this:

Using 2008 as a reference year, US$358,143 and $28,217 was spent annually on the conservation and management of cowpea and wild Vigna. The capital cost took the major share of the costs, followed by quasi-fixed costs for scientific staff, nontechnical labor, and nonlabor supplies and consumables. Each accession cost about $72 for cowpea and only about half of that for wild Vigna.

Now, if you know that there are something like 15,000 cowpeas in IITA’s collection, and multiply that by $72, you can very quickly see that you don’t get $386,000, and you might just start to feel justified in losing confidence in the whole exercise.

So what’s going on? Well, what’s going on, when you look into the numbers, 1 is that the “per accession cost” of $72 was calculated by adding up the individual per accession costs incurred for a set of about a dozen different genebank activities (from acquisition to information management to distribution), and the numbers of accessions involved in each of these was quite different, ranging from 0 for acquisition to 15,000 for long-term storage. So, for example, 475 accessions were distributed at a per accession cost of $22; 2,360 germination tested at $6 a pop etc. Add up all of these per accession costs, as incurred in 2008, and you get $72, for a total of about $386,000.

So, I’m not sure if that $72 really has much of a meaning, but at least now you know how it was calculated. Which maybe the writer of the original piece should have explained.

Mellow fruitfulness on sale

Taro resistant to leaf blight ready to go

Over at Pestnet, plant protection experts are wondering why taro varieties resistant to leaf blight are just sitting around in Pacific genebanks rather than making their way to Cameroon, where the disease has just been spotted.

I find it quite quite extraordinary that we cannot attract donor support to avert a food crisis in Cameroon. The varieties they need are already in PNG and Samoa –- the result of donor funded programmes. Other plant health issues like viruses have also been largely sorted –- again by donor funding. A lot of the material is sitting in tissue culture waiting to go. What is the sticking point to get some over there? What about Alocasia that became a staple in Samoa over the shortage there. That would probably be a quicker and more reliable option than plantain which as we know has enough of its own problems in Africa, including the resident black leaf streak which caused a food crisis in its own right when it arrived there. What is now needed to get it moving.

Is it intellectual property issues? Or just ignorance of the existence of these varieties?

FAO puts crop calendars online

An interesting new feature from FAO’s seeds group:

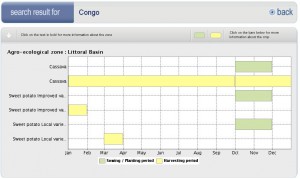

The Crop Calendar provides information about sowing and planting seasons and agronomic practices of the crops grown by farmers in a particular agro-ecological zone. It is a tool developed to assist farmers, extension workers, civil society and the private sector to be able to access and make available quality seeds of specific crop varieties for a particular agro-ecological zone at the appropriate sowing/planting season. It can be used by development-aid workers in the planning and implementation of seed relief and rehabilitation activities following natural or human-led disasters. Furthermore, the Crop Calendar can serve as a quick reference tool in selecting crop varieties to adapt to changing weather patterns accelerated by climate change.

The Crop Calendar database is being maintained at a regional level and is based on inputs from member countries. The Crop Calendar database currently covers 43 African countries and contains information on more than 130 crops, located in 283 agro-ecological zones.

I hope member countries will be encouraged to do what Congo did for sweet potato, which is to record the calendar data separately for improved and local varieties.

I hope member countries will be encouraged to do what Congo did for sweet potato, which is to record the calendar data separately for improved and local varieties.