- “…WFP’s partnership with the Millennium Villages Project would deploy the full range of the Programme’s tools and help utilize the Millennium Villages as a platform for best practices.” Good. But let’s just hope the villagers’ own best tool — agrobiodiversity — doesn’t get left behind.

- More on the Cotacachi agroecotourism project in Ecuador.

- Heritage tourism in the Virgin Islands targets old sugar cane mill.

- The “mango villages” of India.

- Pollination needs to go wild.

- Ok, so the CGIAR is going to re-organize itself into mega-programmes (look at the PDF at the bottom of the page), one of which is on “Crop germplasm conservation, enhancement and use.” Big deal? I wish I knew.

- Pssst, wanna discuss grape breeding?

- More from IIED on landraces and climate change.

- Deforestation, drought and politics in Kenya.

- Tracking eel migrations.

Featured: More on “Conservation for a New Era”

Eve Emshwiller agrees with Nigel:

Thank you, Nigel, for highlighting the critical need to integrate biodiversity and agro-biodiversity conservation and the question of how to do that. It does indeed seem that the McNeely and Mainka publication provides little more than continued lip service (although admittedly that is better than ignoring the issue altogether).

Peter Matthews makes a plea for ‘biocultural diversity’:

Wild species that are related to cultivated crops (and wild plant varieties that are taxonomically placed within cultivated species) do fall into a hole between disciplines, exactly as Nigel states. But not only are they and their habitats and ecological associations neglected, so are the past and present relationships between people and those wild species and varieties.

Matthew Cawood talks integration:

Agreed, focusing on “agrobiodiversity” without considering “biodiversity” is to make the modern mistake of putting these two topics into separate intellectual silos. They are ultimately the same thing.

Read all the comments on IUCN’s “Conservation for a New Era” book and how it dealt with agrobiodiversity.

Nibbles: Gary Nabhan, Poppies, Gates and Worldwatch, Vavilov update, Aquaponics

- “His piped cowboy shirt and vest made my westy heart ache with thoughts of home, and the intensity of his commitment to bringing variety back to our land and our table was inspiring…” I bet it was.

- “The briefing note apparently anticipates a public-relations battle over planting poppies on the Prairies.” I bet it does.

- “You ask if the money might have been better spent supporting the dissemination of this proven knowledge within Africa.” I bet they did.

- Cassava processing in Africa. Lots of people betting on this.

- Vavilov finds enormous onions in Algeria. Who wants to bet they’re still there?

- Aquaponics catching on in Hawaii? You bet.

Mapping livelihoods diversity in East Africa

![]() As the world discusses desertification and worries about the drought in East Africa, it’s as well to remember that it is livestock keepers that bear the brunt of these problems. A recent paper in Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment helps to quantify the size of the challenge. 1

As the world discusses desertification and worries about the drought in East Africa, it’s as well to remember that it is livestock keepers that bear the brunt of these problems. A recent paper in Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment helps to quantify the size of the challenge. 1

It uses environmental and livelihoods data to map the geographic distribution of different livestock-keeping strategies in East Africa. The authors — a team lead by FAO — conclude that:

…nearly 40% of all livestock in the IGAD region are kept in mixed farming areas, where they contribute to rural livelihoods in diverse ways, not least by enhancing crop production through manure and draught power and by providing additional indirect inputs to livelihoods that are seldom properly accounted for. Moreover, an estimated 50 million rural people in Eastern Africa — over a third of the rural population — live in areas where livestock predominate over crops as a source of income. Investment statistics would suggest that this fact often fails to be appreciated fully by governments, donors and policy makers.

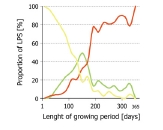

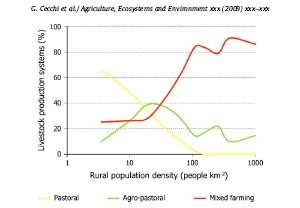

The map itself will hopefully prove useful in guiding policy in the future, 2 but I want to concentrate here on some of the analysis that having all these data in a GIS allowed. In particular, look at graphs of the prevalence of different livelihoods strategies plotted against human population density, and then length of growing period. 3A pastoral production system is where total household income from livestock (L) is 4 or more times greater than total household income from crops (C). An agro-pastoral system has a L/C ratio of 1-4. And in a mixed farming production system the income from crops exceeds that from livestock (L/C<1).[/efn_note]

It looks like areas with a human population density of 20-30 people per square kilometer and a growing season of about 150 days are the most diverse in terms of production systems. It would be interesting to know whether they are also most diverse at the species and genetic levels, for either crops or livestock. I suspect the necessary data weren’t collected in the livelihoods surveys that formed the basis of this study. Will no enterprising student go in and test the hypothesis?

Of collapse and restoration

There’s a new paper by Jared Diamond out, always a welcome event. Alas, it is behind a paywall at Nature, but it is fairly easily summarized. Drawing on recent studies of the collapse of Classic Mayan civilization in Central America and Angkor in Cambodia, and the rise of the Inka empire in the Andes, it makes two main points. One, that civilizations may collapse for multifarious reasons, but “human overexploitation of natural resources never helps.” Two, that “climate can change in either direction.” Not particularly novel or surprising conclusions, but Diamond does his usual slick job of marshaling disparate, multidisciplinary evidence from tourism hotspots all over the world and from throughout history to advance arguments of great contemporary relevance, slight whiff of environmental determinism notwithstanding.

In this case, what struck me particularly was the success story. That is, how climatic change after AD 1100, during the Northern Hemisphere’s Medieval Warm Period, may have helped the Inka’s conquests. The argument is that higher temperatures allowed them to extend agriculture to higher altitudes, increase their arable-land area and make more use of irrigation, leading to greater production and the possibility of feeding large armies. Of course, “military and administrative organization was essential to their conquests, [but] climate amelioration played a part.”

The evidence for agricultural expansion comes from the work of Alex Chepstow-Lusty and colleagues, who analyzed the pollen and other plant parts (and, indeed, other organisms) in mud cores from a high-altitude Andean lake bed. Some of the plant parts came from an alder-like tree. I had no idea that the Inka planted the nitrogen-fixing Alnus acuminata. Its remains increase in lake sediments dated from about AD 1100, along with ambient temperatures and the bodies of llama dung-eating mites, showing that there was starting to be more agriculture and livestock-keeping around the lake at that time.

The success story came to an end, of course. The Spanish cut most of alders down for fuel. Chepstow-Lusty is calling for “massive reintroduction of native tree varieties, such as the alder, to trap moisture blowing over from the Peruvian Amazon to the east. He also recommends repair of the now derelict Incan canals and terraces so they can once again support agriculture.” Have there been similar suggestions for the restoration of the agricultural infrastructure — physical and biological — of the Maya and Khmer? Maybe all the tourists could be put to work on this — or at least tapped for cash.