Here is a video about the life and work of Carlos Ochoa, the recently deceased potato man. By the Televisión Nacional del Perú, in Spanish. From his early days in Cusco, resisting a father that wanted him to become a lawyer, to the agony of an approaching end, with so much of his life’s work unfinished. Watch, listen, admire, and shiver.

Orange revolution

Sweetpotatoes come in different colors and tastes (and sizes). The “yams” eaten in the United States are sweet and have orange and moist flesh. The staple of parts of Africa and the Pacific (and pig feed in China), is typically white-fleshed and not very sweet nor moist (notwithstanding variations like this purple variety.)

Anyway, the orange fleshed sweetpotato is stacked with beta-carotene, the stuff you need to eat for your body to make vitamin A. Many poor people have vitamin A deficiencies, which leads to stunted growth and blindness. So why don’t the poor sweetpotato eaters eat orange fleshed varieties? In part because they simply do not have them, or know about their health benefits. In part because they do not grow well in Africa (decimated by pests and diseases). And also because they do not taste right: too sweet for a staple.

The International Potato Center and partners have been trying to fix all that. Now they have made a nice video about getting orange-fleshed sweetpotatoes into the food-chain in Mozambique. The orange revolution:

https://vimeo.com/2278794I wonder if they also promote mixing more sweetpotato leaves into the diet — even of white fleshed varieties. The leaves are a very good source of micro-nutrients, including beta-carotene! More fodder for the biofortification discussion.

Carlos Ochoa

Carlos Ochoa — legendary potato breeder, explorer and scholar — has passed away at an age of 79 in Lima, Peru.

Born in Cusco, Peru, Ochoa received degrees from the Universidad San Simon, Cochabamba, Bolivia and from the University of Minnesota, USA. For a long time Ochoa worked as a potato breeder. He combined Peruvian with European and American potatoes to produce new cultivars that are grown throughout Peru.

Ochoa was professor emeritus of the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Peru. In 1971, he joined the International Potato Center, where he worked on the systematics of Andean cultivated and wild potatoes. His long list of publications on this topic include hefty monographs on the potatoes of Bolivia and on the wild potatoes of Peru.

His last major published work (2006) is a book on the ethnobotany of Peru, co-authored with Donald Ugent.

Ochoa was a wild potato explorer par excellence. One third of the nearly 200 wild potato species were first described by him.

Carlos Ochoa received many international accolades, including Distinguished Economic Botanist, the William Brown award for Plant Genetic Resources, and, together with long time collaborator Alberto Salas, the Order of Merit of the Diplomatic Service of Peru.

Here is Ochoa’s own story about some of his early work, including his search for Chilean potatoes described by Darwin and his thoughts on potato varieties: “[they] are like children: you name them, and in turn, they give you a great deal of satisfaction”.

¡Muchas gracias, professor!

Over-utilized crops?

Thinking about biofortification, I imagined a world that relies on fewer and fewer over-utilized crops. When will 95% of our food come from two or three of them? Perhaps a maize-arabidobsis hybrid, a cassava wunderroot, and super-rice? Shouldn’t we rather buck that trend and diversify agriculture? That message comes from several corners, like this one: “a food system that is good for us, our communities and the planet is small-scale, diversified agriculture.”

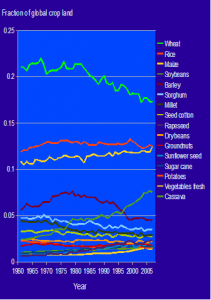

I checked 1 the FAO statistics to see how bad things are going. How quickly are we un-diversifying agriculture? If you consider the fraction of crop land planted to different crops, it appears that — at the global scale — the opposite of what I expected is happening. Between 1961 and 2007, maize and soybean area went up, but that was countered by the decline in the area planted with wheat and barley. 2 It is a story of both winners and losers, and — overall — an increase in diversity.

I checked 1 the FAO statistics to see how bad things are going. How quickly are we un-diversifying agriculture? If you consider the fraction of crop land planted to different crops, it appears that — at the global scale — the opposite of what I expected is happening. Between 1961 and 2007, maize and soybean area went up, but that was countered by the decline in the area planted with wheat and barley. 2 It is a story of both winners and losers, and — overall — an increase in diversity.

Global crop diversity, expressed as the relative amount of land planted to different crops, did not change much between 1961 and 1980, but is has increased since. Between 1980 and 2007, the Shannon index of diversity went up from 3.14 to 3.34.

Do tell me why I am wrong. Is it a matter of scale? Global level diversification of crops while these crops are increasingly geographically concentrated? Could be. Is the diversity index too sensitive to the relative decline in wheat? Perhaps. Or are we really in a phase of (re-) diversification, at least in terms of the relative amount of land planted to different crop species? 3 I cannot dismiss that possibility. For example, I have heard several people speak about on-going diversification (away from rice) in India and China. Has anyone looked at this, and related global consumption patterns, in detail?

Food crisis almost over, people starving as usual

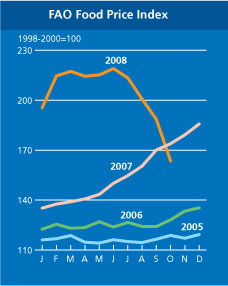

Agriculture related press releases continue to start with a sentences like “The current crisis in world food prices…”. Take these three of yesterday’s posts on this blog: the above quote is from the article discussed in Great Expectations; we need induced mutations because: “The global nature of the food crisis is unprecedented”; and it is also a reason to go forth and grow halophytes: “There’s a real urgency to addressing the issue of rising food and fuel prices.”

Agriculture related press releases continue to start with a sentences like “The current crisis in world food prices…”. Take these three of yesterday’s posts on this blog: the above quote is from the article discussed in Great Expectations; we need induced mutations because: “The global nature of the food crisis is unprecedented”; and it is also a reason to go forth and grow halophytes: “There’s a real urgency to addressing the issue of rising food and fuel prices.”

Haven’t they noticed that the crisis is (almost) over? Supply is up and speculators are retracting. The first stories about complaining farmers are coming in. Perhaps I am missing the point of the long term trend of dearer oil (fertilizer) and climate change?

Either way, in a couple of months we’ll be back to business as usual. Cheap food, and,

every day, almost 16,000 children that die from hunger-related causes — one child every five seconds.