- Quality characteristics of biscuits prepared from finger millet seed coat based composite flour. They’re nutritious. Crocodile Dundee on the tastiness of the iguana may, however, apply.

- Minerals and trace elements in a collection of wheat landraces from the Canary Islands. There are differences, but environment and agronomic practices could affect them.

- Lowering carbon footprint of durum wheat by diversifying cropping systems. Yes, by 7-34%, depending on how the diversification was done.

- Effect of shading by baobab (Adansonia digitata) and néré (Parkia biglobosa) on yields of millet (Pennisetum glaucum) and taro (Colocasia esculenta) in parkland systems in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Taro is a shade lover; grow it under néré, and vice versa.

- Ethnobotanical, morphological, phytochemical and molecular evidence for the incipient domestication of Epazote (Chenopodium ambrosioides L.: Chenopodiaceae) in a semi-arid region of Mexico. Good to know; I love epazote.

- Grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L.) from the Balearic Islands: genetic characterization and relationship with Iberian Peninsula and Mediterranean Basin. See the grand sweep of European history unfold.

- Microsatellite characterization of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) genetic diversity in Asturias (Northern Spain). No evidence of communication with the previous group.

- Plant economy of the first farmers of central Belgium (Linearbandkeramik, 5200–5000 b.c.). They were dope fiends.

- Selection for earlier flowering crop associated with climatic variations in the Sahel. Compared to 1976 millet samples, samples collected in 2003 had shorter lifecycle (due to an early flowering allele at the PHYC locus increasing in frequency), and a reduction in plant and spike size. So you don’t need new varieties, the old ones will adapt to climate change. Oh, and BTW, there’s been no genetic erosion.

- Do species’ traits predict recent shifts at expanding range edges? No.

- The domestication syndrome genes responsible for the major changes in plant form in the Triticeae crops. Failure to disarticulate and 6-rows in barley, in detail. Part of a Special Issue on Barley.

- The genetics of colour in fat-tailed sheep: a review. I didn’t know karakul had fat tails.

Yale announces “Open Access” policy

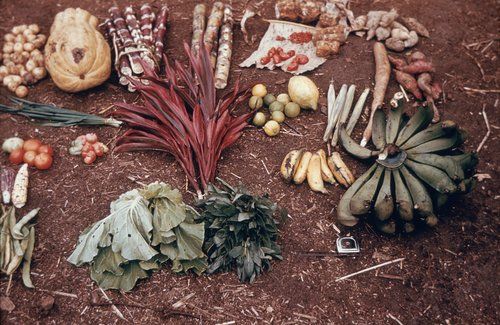

We are happy to celebrate the announcement by Yale University that it is allowing “free access to online images of millions of objects housed in Yale’s museums, archives, and libraries” by reproducing this slide of

Produce of the native agriculture showing bananas, lemons, sweet potatoes, manioc, peppers, sugar cane, squash, lettuce, a spinach type of green, tomatoes, onion, potatoes, maize, and beans. In the center of the picture there is a plant used in black magic (red colored). 1954. Kamu Valley. Kapauku. (Mr. Leopold Pospisil’s collection of slides on the Kapauku Papuans of New Guinea.)

Plenty more in there of agrobiodiversity interest.

Nibbles: Fruit-tree fundraiser, Bangladesh seed crisis, Mead, Early farmers, Fruit genebank

- Bioversity promotes a fund-raiser for forgotten fruit trees.

- Seed crisis in Bangladesh. It’s complicated. Really complicated.

- Belatedly, mirthful report on mead.

- “…during the advent of agriculture … early farmers may have at first come together in communal activities, prior to congregating in villages.”

- USDA’s fruit genebank at Corvallis in the news.

Agriculture and people

So, “agricultural expansion is the principal factor for shaping global linguistic diversity,” and indeed human genetic diversity, both in Europe and Japan. Further evidence for Bellwood’s controversial thesis.

Yes, why not, the oldest horse breed in the world

Quick, what’s the oldest horse breed still in existence? Well, apparently, it’s the Caspian or Māzandarān Horse, and remains have recently been found in a cemetery dating back to 3400 BCE. Perhaps I should find it hard to believe one can recognize a breed from a skeleton, but I choose to suspend any disbelief I may have, because I like the story.

The Caspian horse was thought to have disappeared into antiquity, until 1965 when the American wife of an Iranian aristocrat called Louise Firouz went on an expedition on horseback and discovered small horses in the Iranian mountainous regions south of the Caspian Sea.

It happens to be very genetically diverse, which may suggest survival of wild horses in a Holocene refugium. Will they try to extract ancient DNA from the skeleton? Gosh, I do hope so. Via.