- Unpacking the heat of chillies.

- Debating pastoralism, a new journal.

- Celebrating (instead of growing?) yams.

- Economic Botany releases free download of paper on caimito domestication.

- More than 50,000 people care about Pavlovsk Experiment Station. Unstoppable?

- A bean diversity fair was held in Uganda on the 21st of June 2010. Did we miss it then?

- Searching for the Blue Zebra … tomato. Wonder if AVRDC know about it.

- Those blogging diplomats — How to make a scarf from a tree.

- Tibet’s disappearing grasslands. Pastoralists see item 2 above.

- IRRI DG says, in Latin America, that Latin America could be next global rice bowl. Well, he would, wouldn’t he. Very data-heavy presentation.

- One VERY remote sunflower wild relative. Very cool.

- Chaffey’s regular words of wisdom on anything botanical. Well, mostly wise. But more on that later…

- The history of the apple in the early US.

- IUCN does for African freshwater fish what it does best. Ring the alarm bell.

The Importance of Scientific Collections

The American Institute of Biological Sciences and the Ecological Society of America are among the scientific organizations around the world that have urged the Russian Federation to reconsider the decision to destroy the collections at the Pavlovsk Experiment Station. And they remind us that we do occasionally need to relate our concerns about agricultural biodiversity to wider concerns about biodiversity: it isn’t only our favoured collections that are threatened.

Lack of funds, loss of technically trained staff and inadequate protection against natural disasters, are jeopardizing natural science collections worldwide. For example, in May of this year an accidental fire destroyed roughly 80,000 of the 500,000 venomous snake-and an estimated 450,000 spider and scorpion-specimens at the Butantan Institute in São Paolo, Brazil. The 100-year-old collection featured some rare and extinct species and contributed to the development of numerous vaccines, serums and antivenoms. The building that housed these specimens, including what may have been the largest collection of snakes in the world, lacked fire alarm or sprinkler systems.

“Biological collections, whether living or non-living, are vitally important to humanity,” says Dr. Joseph Travis, president of the American Institute of Biological Sciences. “Natural science collections have provided insights into a wide variety of biological issues and pressing societal problems. These research centers help identify new food sources, develop treatments for disease and suggest how to control invasive pests. Natural science collections belong to the world and cannot be limited by geographic borders.”

Good points, well made.

Getting the most out of wild tomatoes

![]() Where should breeders look for traits like drought resistance among the landraces and wild relatives of crops? The FIGS crowd says: in dry places, of course. And they have a point. But it may not be as simple as that, as a recent paper on wild tomatoes shows. ((XIA, H., CAMUS-KULANDAIVELU, L., STEPHAN, W., TELLIER, A., & ZHANG, Z. (2010). Nucleotide diversity patterns of local adaptation at drought-related candidate genes in wild tomatoes Molecular Ecology DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04762.x))

Where should breeders look for traits like drought resistance among the landraces and wild relatives of crops? The FIGS crowd says: in dry places, of course. And they have a point. But it may not be as simple as that, as a recent paper on wild tomatoes shows. ((XIA, H., CAMUS-KULANDAIVELU, L., STEPHAN, W., TELLIER, A., & ZHANG, Z. (2010). Nucleotide diversity patterns of local adaptation at drought-related candidate genes in wild tomatoes Molecular Ecology DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04762.x))

The authors looked at the diversity of two genes implicated in drought tolerance, nucleotide by nucleotide, in three populations of each of two closely related wild tomato species from the arid coastal areas of central Peru to northern Chile. Annual precipitation at the collecting sites ranged from 5 to 235 mm. As another recent paper put it, the tomato genepool “has both the requisite genetic tools and ecological diversity to address the genetics of drought responses, both for plant breeding and evolutionary perspectives.” Here’s where the populations came from: 1-3 are Solanum peruvianum, 4-6 are S. chilense.

These places are pretty dry. Here’s what a close-up of the driest (number 3) looks like:

Anyway, Hui Xia et al. found evidence of purifying or stabilizing selection at one gene, called LeNCED1. So far so good. But they also found a pattern of variation at the other gene, pLC30-15, in one of the populations (number 4, S. chilense from Quicacha in southern Peru) which they interpreted as evidence of diversifying selection, where “two alleles compete against each other in the fixation process.”

Now, that would arguably be a more interesting population for a breeder to investigate than any of the others, but the observation “is difficult to explain based on the environmental variables of the populations investigated.” Ouch, say the FIGS crowd! ((Actually, it’s not as bad as that, that other paper I quoted earlier has this to say: “We confirmed that several eco-physiological traits show significant trait-climate associations among climate-differentiated populations of S. pimpinellifolium, including strong association between native precipitation and whole-plant tolerance to water stress.”)) But is it perhaps that the authors just considered average rainfall, and not how variable rainfall was at the site, from year to year? The best they can suggest by way of explanation is that S. chilense is an endemic with a very narrow ecological amplitude. In contrast, S. peruvianum is more of a generalist, with larger, expanding populations, found in both dry and mesic locations: “this may not be favourable for the occurrence of adaptive evolution, either because phenotypic plasticity can be promoted rather than local adaptation or because beneficial mutations are more likely recruited from the higher genetic standing variation.”

So, target dry areas for adaptation to drought tolerance, by all means, but the environment is not all, and some wild species may be more useful than others in providing interesting diversity depending on their ecological strategies and population dynamics.

Cattle’s great adventure

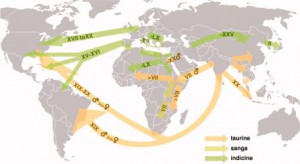

![]() Evolutionary Anthropology has a nice paper summarizing the history of domestic cattle, based on the latest molecular marker data. ((Ajmone-Marsan, P., Garcia, J., & Lenstra, J. (2010). On the origin of cattle: How aurochs became cattle and colonized the world Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 19 (4), 148-157 DOI: 10.1002/evan.20267)) Unusually, the authors at least attempt a flowing account of the origin and spread of a domesticated species, and even more unusually actually achieve it in places. Alas, the details of haplogroups and mtDNA vs Y-chromosome markers will keep intruding. Someone will write a review paper some day which gets the geeky stuff of summarizing all the molecular and other data out of the way upfront, and then just tells the story of domestication and dispersal as the old-fashioned, and no doubt now out of fashion, narrative historians used to do. Rather than annoyingly mixing up the two.

Evolutionary Anthropology has a nice paper summarizing the history of domestic cattle, based on the latest molecular marker data. ((Ajmone-Marsan, P., Garcia, J., & Lenstra, J. (2010). On the origin of cattle: How aurochs became cattle and colonized the world Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 19 (4), 148-157 DOI: 10.1002/evan.20267)) Unusually, the authors at least attempt a flowing account of the origin and spread of a domesticated species, and even more unusually actually achieve it in places. Alas, the details of haplogroups and mtDNA vs Y-chromosome markers will keep intruding. Someone will write a review paper some day which gets the geeky stuff of summarizing all the molecular and other data out of the way upfront, and then just tells the story of domestication and dispersal as the old-fashioned, and no doubt now out of fashion, narrative historians used to do. Rather than annoyingly mixing up the two.

Anyway, that story can be summarized for cattle in one map, and here it is:

Which is cool enough. But actually what stays in the mind — or, at any rate, my mind — is, as ever, the little things. Here are three that did it for me.

First, a rare attempt to link up genetic patterns in a domesticated species and the associated human population:

Four ancient Tuscan breeds all had haplotypes also found in Anatolia, near the sites of domestication. [This] … may indicate a secondary migration from Anatolia to Italy, [which] … would be in line with the classical accounts of Etruscans arriving in Italy from either Lydia or the isle of Lemnos. An Etruscan representation of cattle resembles the semi-feral Maremmana cattle in southern Tuscany. Interestingly, inhabitants of two small Tuscan cities with Etruscan origins also had southwest-Asian mtDNA signatures.

Second, a simple historical explanation for a fairly obvious feature of modern European cattle diversity, to wit, that there isn’t much of it in the Netherlands.

Seventeenth-century Dutch paintings show cattle with a large variety of coat colors. After three catastrophic rinderpest epidemics in the eighteenth century, cattle herds were repopulated by mass imports of black-pied cattle from the Holstein region.

And finally, the story of the Brazilian zebu herd, which caught my eye because of the reference to it in a recent Economist article.

This started during the nineteenth century with the purchase of a few animals and was followed by mass imports of Guzerat (1975), Gir (1890), and Ongole (1895, in Brazil denoted as Nelore) animals to improve the national herds. The same zebu breeds were also imported into the U.S. These imports consisted mainly of bulls. The percentage of animals with zebu mtDNA varies in Brazil from 37% in the Gir breed to 43% in the Nelore and 69% in the Guzerat breeds. As shown by the distribution of the indicine Y-chromosomes and microsatellite analysis, zebu bulls were crossed in several South American Criollo populations… Today, Brazil holds the largest commercial cattle population worldwide, with 200 million heads. Together with descendants of other indicine and taurine imports, Nelore make up the bulk of this intensively managed population.

You see what I mean about the geeky stuff interrupting the flow, right? Anyway, the particularly fun detail about this Brazilian zebu story is the fact that one Nelore bull, called Karvadi, “became the ancestor of thousands of Brazilian zebu cattle.” There’s a photograph of him in the paper, courtesy of the Archives of the VR Artificial Insemination Center, Araçatuba, and very handsome he is too.

10 of Europe’s best under-the-radar food festivals

Last Sunday’s Observer magazine listed 10 food festivals across Europe. As ever, if you go, we’ll be happy to publish a report. Personally, the Fête des Legumes Oubliés would be my preference. But then there’s the Festa della Zucca, closer to home, and the Piment d’Espelette Festival in France, which we’ve blogged about before. The one I really want to go to, not mentioned by The Observer, is the Fiesta de la Alubia in Tolosa. I can’t find much about it now, but I vividly remember from my most recent trip to Gipuzkoa the potential of being inducted as a Knight of the Alubia. That appeals. As do the beans, among the finest known to humanity.