- Head of Convention on Biological Diversity says nothing to Reuters about climate change and agriculture.

- Link farm lists Top 50 Botany Blogs. We reciprocate.

- “[M]ost of us are the beneficiaries of millennia of acclimatization“. Rachel disses the Columbian Exchange.

- “Men didn’t grind, let alone gentlemen.” Rachel disses Iberian explorers.

- Back40 has a beef with supermarket nonsense. There is grass-fed beef in America.

- The Naked Pint: beers gone wild

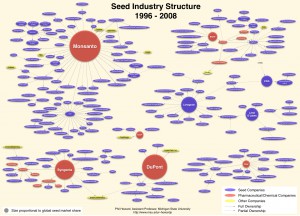

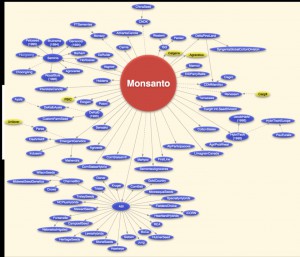

Visualizing Consolidation in the Global Seed Industry: 1996–2008

Where is agriculture

It was barely in evidence in the original text for the Copenhagen Climate change meeting, though there are hopeful signs that it may be creeping in. Now comes further evidence that the world at large, or at least the rich, well-fed world, basically doesn’t give a stuff about agriculture. 2010 is the official United Nations International Year of Biodiversity. And it must be important, because it has a couple of Facebook pages and a Facebook group.

You’re wondering, do either of those mention agriculture, even fleetingly? would I be here if they did?

Nibbles: Forests, Climate change, Campaign, Water chestnuts, Research, Fruit

- “Countries can clear massive amounts of forest and still claim that deforestation had not occurred“. Wha?

- Biodiverse agriculture to meet climate challenge. Really?

- Diversity for Life campaign launches, but Official Site links to wrong Offical Site. This is where it should go.

- Water chestnuts. Fascinating.

- No sign of agricultural biodiversity in agricultural research masterplan.

- Vital Christmas supplies of Crataegus mexicana — aka Tejocote — no longer illegal in the US. h/t Rachel.

Agriculture hits limelight in Copenhagen. Maybe.

Today’s the big day for agriculture in Copenhagen. A lot is riding on it, because there hasn’t been much sign of interest at UNFCCC COP15 up to now in the subject of how agriculture is going to adapt to climate change. You can follow Cary Fowler’s Notes from Copenhagen on Facebook.