- Cicadas are good, and good for you.

- Genes from “foreign” wheat played significant role in improving Chinese wheat.

- Spain publishes plan for the conservation, improvement and promotion of livestock breeds.

- Milk Matters. To Somali children in Ethiopia, in this case.

- Winners of ACSS awards for 2009 announced.

- “Conserving Ethiopia’s biodiversity far from adequate.” Or so says Ethiopia’s report to CBD. Some agrobiodiversity included.

- New Agriculturalist is out. Rejoice.

- Andy Jarvis on the value of geo-referencing.

Nibbles: Forest fires, integration

- Fire-fighters should heed forest diversity. Now there’s a thought.

- “Resilient integration of industrial and organic agriculture.” Now there’s a thought.

Nibbles: Climate, Fertilizers

- Sustainable Agriculture: The Unrecognized Key to Reversing Climate Change. Unrecognized by whom?

- Fred Pearce says: Cold turkey on nitrogen, now. It’s our only hope.

Tracking down rice genetic erosion numbers

So, Olivier de Schutter, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, who teaches at the University of Louvain in Belgium and Columbia University in the United States, has been talking to reporters about the dangers of genetic erosion:

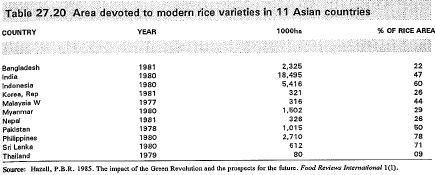

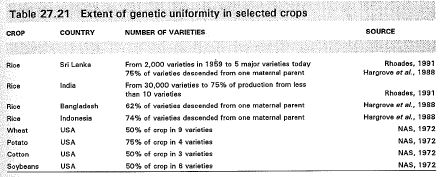

He noted that in Sri Lanka in 1959, for example, some 2,000 varieties of rice were cultivated, whereas today, there are fewer than 100, and some 75 per cent of agro-biodiversity has been lost as a result of the pressure towards to the adoption of uniform improved seed varieties.

We know where the 75% figures comes from, and that it is, frankly, rubbish. What about the other two?

Two thousand Sri Lankan landraces is not implausible. There are 2028 rice landrace accessions in the IRRI genebank, 25 of which have georeferences. So, with various caveats, if I didn’t have any other information, I wouldn’t feel too uncomfortable about using that number for the pre-Green Revolution diversity of rice in that country.

But actually there is other information. The full version of de Schutter’s report, which he kindly sent us, had a reference for the number ((Groombridge, B. World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge (UK). 1992. Global biodiversity. Status of the earth’s living resources.)), and thanks to our friend Maria Garruccio at the Bioversity International library we tracked it down. It in turn gives the number as coming from Part 2 of the book “Uses and Values of Biodiversity,” under the section “Biodiversity and Economics,” pages 426-427. The information can be found in a couple of tables.

So that sent us to R.E. Rhoades‘ 1991 article in National Geographic “The world’s food supply at risk” ((National Geographic Magazine 179(4): 74-105.)) This is a new one on me. Here’s the relevant bit:

In Sri Lanka, where farmers grew some 2 ,000 traditional varieties of rice as recently as 1959, only five principal varieties are grown today. In India, which once had 30,000 varieties of rice, more than 75 percent of total production comes from fewer than ten varieties.

Alas, there’s no reference given for those numbers, but I’m pursuing this further. Prof. Rhoades is not listed as a rice donor to IRRI, though he did work at CIP for some years. But his companion during his trip to Sri Lanka for National Geographic, Balendira Soma Sundaram ((The article refers to him as “the country’s chief plant explorer.”)) is, according to IRRI’s databases, a collector of 257 accessions from 3 IRRI collecting missions to that country (1979, 1984, 1988). So he should know.

Incidentally, some 60 improved rice varieties have been released in Sri Lanka since 1964 again according to IRRI’s database. INGER monitors such things.

Not just hungry, sick

While not strictly about agricultural biodiversity (although much more could be made of agrobiodiversity in this realm) Scidev.net draws attention to an editorial in The Lancet. ((Which requires free registration to read in its entirety.)) In the run up to (yet another) High Level Summit — this time on Food Security — next week, Scidev.net reports The Lancet’s view that:

Poor terminology adds to the problem — calling undernourished people ‘hungry’ is belittling. Even the term ‘undernourished’ can be confusing to policymakers, says the editorial.

Really? How easily confused those policymakers must be.

It adds that medicalising food — where undernutrition is the disease and food the treatment — could make ensuring food supplies a bigger priority for the global health sector.

Again, because the world has such a good record of delivering global health care to those who need it most?

Climate change gets a namecheck too, natch. And if I sound just a teeny bit cynical, maybe that’s a sickness too.