- Songs raise awareness about aquatic invasive species. Jeremy says: Kill me now.

- Long, long post about climate change in Africa. Part 2 “coming soon”.

- Yemen prepares for climate change. Need a “strategy for the promotion of rain-fed agriculture”.

- Bananas from Iceland … Jeremy says: I don’t get it.

- New Agriculturist focuses on natural fibres.

Rokupr rotting away

An opinion piece in the Awareness Times of Sierra Leone decries the current parlous state of Rokupr Agricultural Research Station. It starts, however, by waxing lyrical abut the past.

Established about half a century and decade ago, the Rokupr Rice Research Station was a darling vision of the early colonialists who among other considerations were fascinated by the fertile ecologies and enviable terrain of the Scarcies coastline… With rice as a popular diet in West Africa and around the world, Sierra Leone in the shadows of Rokupr Rice Research was put on the spot light of fame and popularity. Rokupr became internationally known.

Indeed. And not only for rice breeding, but also for being at the forefront of the scientific thinking about on-farm conservation of plant genetic resources in the 1990’s, as part of the Community Biodiversity Development and Conservation Project. Alas,…

…[t]he present condition of Rokupr Rice Research is dismal. The one time elegant roads in the station premises are presently all gorges and death traps. The compound remains uncared for. Trees, shrubs and grass have overgrown and form a canopy over the compound. The trees are dens for giant snakes and other poisonous pests. Research trial fields are abandoned. There are no resident senior staffs and research activities have been suspended for ages. The compound looks marooned and deserted. The aura of research is dilapidated. Laboratories and staff quarters are ransacked and in dear need of renovation. Staff morale, dedication, and motivation are low and devoid of promise.

A pity, especially since an alumnus of the station was minister of agriculture until fairly recently. Who will save Rokupr?

Mapping Ugandan wetlands to protect them

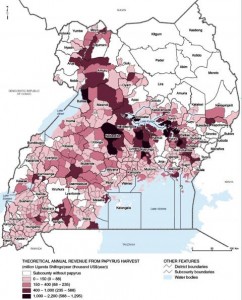

Want to know where Ugandans can make the most money from harvesting papyrus? Here you go:

This map is one of a whole series on Ugandan wetlands — their potential and the threats they face — that has just been published by the World Resources Institute ((In collaboration with Uganda’s Wetlands Management Department, the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, and the International Livestock Research Institute.)) under the title Mapping a Better Future: How Spatial Analysis Can Benefit Wetlands and Reduce Poverty in Uganda.

One of the co-authors, Paul Mafabi , commissioner of the Wetlands Management Department in Uganda’s Ministry of Water and Environment, had this to say at the launch:

These maps and analysis enable us to identify and place an economic value on the nation’s wetlands. They show where wetland management can have the greatest impacts on reducing poverty.

There are probably some wild rice relatives lurking in these wetlands too, let’s not forget.

The end of the line for Egypt Baladi?

The controversy over the Egyptian pig cull is turning very nasty.

There are estimated to be more than 300,000 pigs in Egypt, but the World Health Organisation says there is no evidence there of the animals transmitting swine flu to humans.

Pig-farming and consumption is concentrated in Egypt’s Coptic Christian minority, estimated at 10% of the population.

Many are reared in slum areas by rubbish collectors who use the pigs to dispose of organic waste. They say the cull will harm their businesses and has renewed tensions with Egypt’s Muslim majority.

The Domestic Animal Diversity Information System hosted by FAO records only one pig landrace in Egypt, called Egypt Baladi, from بلاد which just means land or soil. “Baladi” means something like “of this land”. The pig has a long history in Egypt, but I can’t find any information on its genetic affinities. If the total cull goes ahead, will a unique, ancient landrace be lost forever?

“A man is related to all nature”

Mark Easton, the BBC’s home editor, starts a blog post today with this quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson as an introduction to making the point that the protected area of Wicken Fen in Lincolnshire is… ((Thanks to Indrani for the tipoff.))

…the product of complex interaction between plants, birds and animals. And fundamental to its existence were the apparently destructive activities of one animal in particular: man.

Well, that could be said of a lot of landscapes around the world. Even, possibly, as is increasingly argued, places like the Amazon, which until recently was generally regarded as nature in its most pristine state.

But to go back to Wicken Fen, which, incidentally, I remember very fondly, having done a certain amount of fieldwork there as an undergraduate. It seems “the [UK] government, anxious to protect another fragile habitat, the peat bog, wants 90% of composts and soil improvers to be peat-free by next year.” So peat digging was banned at Wicken Fen. Good, you say? Well, not so much. This change in a practice that has been going on for centuries has contributed to the local extinction of the rare fen orchid. And not only that, the fen violet too, probably:

The rural culture – which had cut the sedge for roofing and animal bedding – disappeared and the fen violet along with it. Its seeds may still survive in the peaty soil and occasionally a rare plant will push through the surface if the land has been disturbed, but the violet has not been seen at Wicken for more than a decade.

And the swallowtail butterfly and Montagu’s harrier as well, due to past changes in management practices.

So what to do. As Mark Easton says, nowadays “conservationists ape the principles of the ancient harvesters to protect what is left of the fen.” But not all agree. “Instead of trying to counteract nature, man should work with it.”

This is a much less predictable approach to conservation but, it seems to me, it is a philosophy more in tune with an acceptance that man is not god. We are part of nature too.

Fair enough, but what if you are managing a protected area specifically for a particular species of value? Say an important crop wild relative. I can imagine a situation where you might want to be a bit more intensive in your intervention, and a bit more predictable. Which is one of the reasons why I don’t think that “conventional” protected areas such as your average national park will ever be much use for CWR conservation, except by chance.

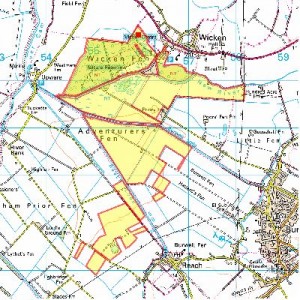

Incidentally, there’s a couple of CWRs at Wicken Fen, according to the great mapping facility on its website. Here’s where you can find Asparagus officinalis, for example: it’s that red square right at the top.