A post over at Biofortified entitled “Will cover crops feed the world?” asked an intriguing question:

Why not take a survey of red clover and hairy vetch germplasm, looking for those that fix nitrogen at high rates, have good winter survival, and decay at a reasonable rate to provide fertilizer for crops the following year, and then combine those traits? (And while you’re at it, you could try to do something about hairy vetch’s horrendous seed yield. Non-shattering trait, anyone?)

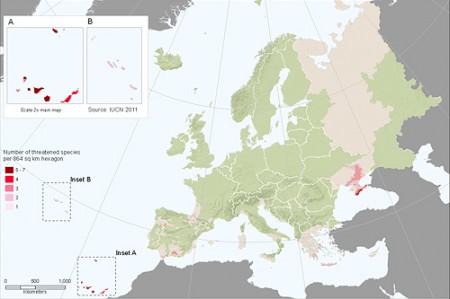

Well, I thought to myself, maybe you can find those traits already combined. So I looked on Genesys to see what germplasm of Vicia villosa, or hairy vetch, we have to play with. Quite a bit as it turns out: 1374 accessions from 60-odd countries, conserved in 30-odd genebanks. These are the accessions which have georeferences:

I looked in a little more detail at the USDA collection over at GRIN. As luck would have it, there are data on 40-odd accessions from a 2001 evaluation trial. Among the descriptors recorded are N content and winter survival. I downloaded the Excel spreadsheet, and some quick sorting revealed a couple of accessions which are both high in N and have decent winter survival, eg PI 232958 from Hungary and PI 220880 from Belgium. Another dataset shows that some accessions in the collection are non-shattering. Alas, neither of the previous two accessions were characterized for that trait, or at least I couldn’t find the data online, but I was intrigued to see that PI 220879, also from Belgium, is non-shattering.

I posted Biofortified’s question on Facebook too and Dirk Enneking came back almost immediately with more advice:

Provorov and Tikhonovich suggest that the recently domesticated species such as Vicia villosa are better at N-fix. For non-shattering, try the named cultivars such as Ostsaat etc. and grow them where there is sufficient humidity at harvest time to reduce shattering.

Now, where’s my finder’s fee?