- Dropping the poppy.

- Gardening on windowsills and along roadsides.

- Cooling camel milk. Via.

- Fingerprinting grapes.

- “The seed banks that are run by agribusiness corporations would be a costly pursuit for the government and farmers.” Where to start responding to this? Thanks, Jeff.

- Further evidence of food price crisis.

- “What does biodiversity mean to Syngenta?“

- Traditional healer goes online. Via.

- Videos from Global Plant Clinic.

SINGER maps crop wild relatives

Putting the new SINGER interface through its paces, I find that it can do something interesting that GRIN cannot. Or at least I can’t see a way of doing it, let me know if you can. Below is a screenshot from SINGER showing a Google Map of the distribution of all wild Arachis accessions that the database knows about which have geographic coordinates. Very useful, I think. GRIN does map localities, but I could not manage to get it to do so for multiple species like this.

Another feel-good crop wild relative story

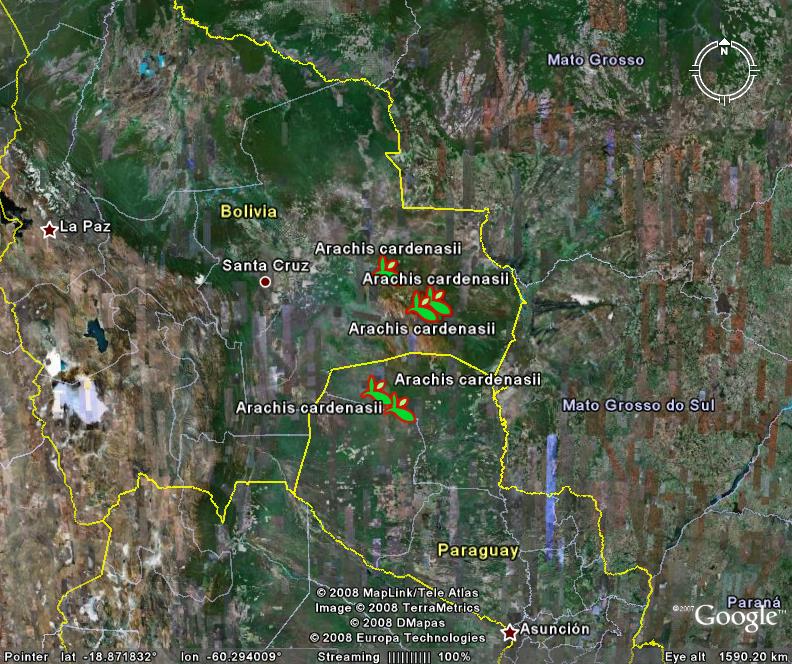

When I saw news stories a short while back about a new peanut variety called Tifguard, famous for having resistance to both peanut root-knot nematode and tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), the main question I had was where the resistance(s) came from. So I consulted our resident peanut expert, and it turns out that the nematode resistance gene in Tifguard came from the variety COAN. Which in turn got it from the wild relative Arachis cardenasii. And by conventional breeding, no less.

Although saying that glosses over the fact that Charles Simpson‘s introgression programme at Texas A&M sometimes involved making more than a thousand meticulous interspecific crosses just to get a single seed. Nobody ever said using crop wild relatives in breeding programmes was easy! Anyway, this is a truly exemplary case of what can be done to incorporate genes from crop wild relatives into improved cultivars using “conventional” breeding methods.

Not much A. cardenasii in GRIN or SINGER. ((Although I’m sorry to say I wasn’t actually able to get SINGER to give me much more than the total number of accessions, and that after a bit of a struggle. Who knows, maybe our resident peanut expert can do something about that. Anyway, do let me know if you have better luck.)) GBIF adds data from a couple of herbaria, but in total we’re talking about no more than about 30 records or so, some of which are no doubt duplicates.

MUCH LATER: Follow-up, with live links!

Nibbles: Ag origins, MSV origins, Land origins, Art,

- Podcast on the origins, history and future of agriculture. “Three annual grasses explain history.” “Wheat domesticated humans.” Etc. Richard Manning gives good value.

- The origin of Maize Streak Virus explored.

- Changes in Dutch agricultural land. More diversity in land use over time.

- More ag art. Via.

Tasteful breeding

A couple of days ago the Evil Fruit Lord complained — a little bit — about an article in a Ugandan newspaper which extolled the virtues of traditional crops and varieties over new-fangled hybrids. While not doubting the many attractive qualities of landraces and heirloom varieties, he quite rightly pointed out that there’s nothing to stop modern varieties and hybrids tasting just as good:

I get really sick of the tendency to talk about plant breeding as a process which makes crops into finicky, crappy tasting garbage in exchange for yield. You absolutely can create varieties which taste as good (or better) than traditional varieties, produce more, and resist pests. In fact, plant breeding is the only way to get to that.

Now there’s an article by Arthur Allen in Smithsonian magazine which basically says — not very surprisingly, I suppose — that both those things have happened in the tomato:

Flavor … has not been a goal of most breeding programs. While importing traits like disease resistance, smaller locules, firmness and thicker fruit into the tomato genome, breeders undoubtedly removed genes influencing taste. In the past, many leading tomato breeders were indifferent to this fact. Today, things are different. Many farmers, responding to consumer demand, are delving into the tomato’s preindustrial past to find the flavors of yesteryear.

Allen has a good word to say for the wild relatives:

The architect of the modern commercial tomato was Charles Rick, a University of California geneticist. In the early 1940s, Rick, studying the tomato’s 12 chromosomes, made it a model for plant genetics. He also reached back into the fruit’s past, making more than a dozen bioprospecting trips to Latin America to recover living wild relatives. There is scarcely a commercially produced tomato that didn’t benefit from Rick’s discoveries. The gene that makes such tomatoes easily fall off the vine, for instance, came from Solanum cheesmaniae, a species that Rick brought back from the Galapagos Islands. Resistances to worms, wilts and viruses were also found in Rick’s menagerie of wild tomatoes.

And he also plugs genebanks:

…we can take comfort in the tomato’s continuing, explosive diversity: the U.S. Department of Agriculture has a library of 5,000 seed varieties, and heirloom and hybrid seed producers promote thousands more varieties in their catalogs.

Not quite sure where he got that number, as the C.M. Rick Tomato Genetic Resources Center seems to have about 3,500 accessions, but anyway.