The latest IUCN assessment of the conservation status of European biodiversity is out, and is making the news. The bit on plants is co-authored by Melanie Bilz, Shelagh P. Kell, Nigel Maxted and Richard V. Lansdown and, unsurprisingly perhaps given their track record, includes, I believe for the first time, extensive discussion of crop wild relatives as a distinct class. ((Other classes of plants dealt with in detail are those “listed in European and international policy instruments” and aquatic plants.)) The authors, which coordinated input from dozens of experts, conclude that out of a total of 591 CWR species:

Within the EU 27, at least 10.5% of the CWR species assessed are threatened, of which at least 3.5% are Critically Endangered, 3.3% Endangered and 3.8% Vulnerable – in addition, 4.0% of the species are considered as Near Threatened. One species, Allium jubatum, is Regionally Extinct within Europe and the EU; it is native to Asiatic Turkey and Bulgaria, but has not been found in Bulgaria since its original collection in 1844.

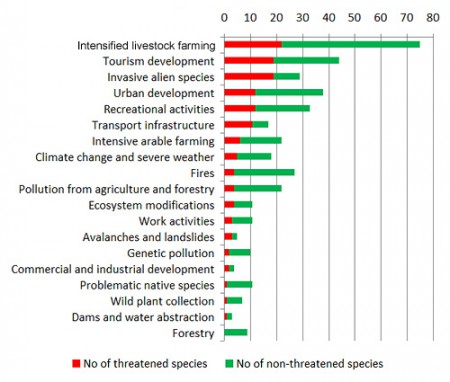

It does not even seem to be available from botanic gardens, according to Botanic Gardens Conservation International’s database. I don’t know what has caused its disappearance in Bulgaria, but currently the main threats to CWRs seem to be intensified livestock farming, tourist development and invasives:

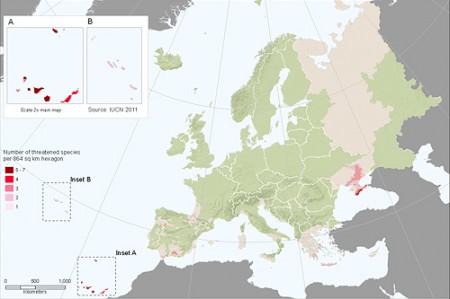

And there are maps ((Which I hope are available in versions one can import into Google Earth, but I haven’t looked into this yet.)) of both the distribution of overall CWR species richness and of the most threatened species:

An extremely useful review is provided of previous work assessing the extent to which CWRs are conserved in genebanks, botanical gardens and protected areas in Europe. But here perhaps I would like to quibble with the authors. Although their listing of existing conservation efforts seems to me thorough and comprehensive, there is no attempt made to synthesize the results of all the different initiatives and come up with a list, however preliminary, of high priority plants for immediate conservation intervention. Surely it would not have been particularly difficult to cross-reference their list of threatened species with listings of accessions in Eurisco and the BGCI database, for example. Maybe this was beyond the scope of this particular exercise and is the focus of parallel work. Perhaps Nigel or Shelagh will respond here.

This is a very important contribution to raising the profile of CWRs within the biodiversity conservation community. Let us hope that it will translate into increased support for their conservation, both ex situ and in situ, along the lines so usefully set out by the authors in their recommendations.

To specifically answer Luigi question is that further analysis was not possible within the context of the IUCN publication, but we have a more detailed analysis that should be out next month:

Kell, S.P., Maxted, N. and Bitz, M. (2011) European crop wild relative threat assessment: knowledge gained and lessons learnt. In: Maxted, N., Dulloo, M.E., Ford-Lloyd, B.V., Frese, L., Iriondo, J.M. and Pinheiro de Carvalho, M.A.A. (eds.) Agrobiodiversity Conservation: Securing the Diversity of Crop Wild Relatives and Landraces. CAB International, Wallingford.

I will circulate it as soon as we have the final pdf.

@Nigel — Thanks, dude.

As Nigel notes, there was limited scope in terms of presentation of results in the IUCN report as it had to adhere to the same format used for the other groups assessed as part of the European Red List.

However, conservation needs are highlighted for each species assessed in the published assessments and in the book chapter that Nigel mentions, there is a summary of conservation needs identified for 483 species of the species assessed. For 446 species, ex situ conservation was highlighted as an immediate priority.

On the whole, we can assume that most of the CWR assessed as threatened are in need of immediate conservation action.

Further analysis will be undertaken and published at a later date.

Also, note that in Chapter 5 of the CABI text, CWR Conservation and Use, an analysis of the representation of European CWR in the Habitats Directive, IPAs, IUCN Red List and Botanic Garden collections was presented.

In the PGR Secure project we are developing a comprehensive conservation strategy for European CWR and this will include a list of high priority species in need of conservation attention at regional level.

PS If someone wants to view individual assessments, say for a crop gene pool, go to the European Red List website (http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/index_en.htm), click on ‘search for a species’, enter a crop genus name and all the species assessed in the that genus will come up. The list of crop genera included is in the European Red List of Vascular Plants publication. Also, all species endemic to Europe (188) are published in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (http://www.iucnredlist.org/).

Thanks very much, Shelagh.

Fascinating stuff. If that PDF is for wider circulation I’d love a copy…

I am concerned about the downside of the in-situ conservation of crop wild relatives, particularly when sponsored by multimillion dollar conservation agencies. These agencies characteristically have an animosity to agriculture and food production, throwing farmers out of reserves (now 14% of global land area, often with a history of farming). CWRs will be an excuse for yet more unproductive land use (`fines and fences’ reserves of extensive farming) or justification for the continuation of failing nature reserves.

Unless we can show that CWRs in-situ are evolving features of value to crop breeding, then ex-situ is far more useful both for controlled evaluation and secure conservation (is there any evidence that CWRs somehow get `better’ over time or are we making some fairly large assumptions?).

Finally, the presence of CWRs equal enhanced hot-spots of pests and disease pressure for the relevant crop. Many countries hosting centres of origin need to import food of the very crops that originated in and around the country (Iraq for wheat, Mexico for maize, China and Japan for soybean, and all (well, nearly all) tropical plantation crops. Is it that major crop production zones do not usually have CWRs of those crops as a source of infection and infestation? (The same can apply to centres of crop diversity with no close wild relatives: somewhere in the large diversity of wheat landraces in Ethiopia Ug99 is lurking).

What’s in it for developing countries? Has anyone explained that CWR conservation in-situ can damage the farming of indigenous varieties? I suggest that this should be far more of an economic issue than the very widespread conservationist concerns over GM `contamination’ of CWRs and crops.

But, of course, I need to read the reports and papers to see if these issues are addressed.