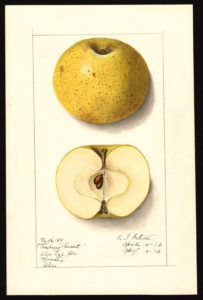

Gayle Volk and Adam Henk of USDA recently published a fascinating article on “Historic American Apple Cultivars: Identification and Availability.” Gayle kindly agreed to summarize it for us. Thanks, Gayle. Oh, and by the way, if you like old pictures of old apples (and other fruits), there’s a mesmerizing Twitter feed for you.

In this work, historic books, publications, and nursery catalogs were used to identify the cultivars that were propagated and grown in the United States prior to 1908. Synonyms, introduction dates, and source country for 891 historic apple cultivars were recorded in total. We then classified them based on their availability over time and popularity in nursery catalogs. We considered the highest priority cultivars for conservation to be those that were actively propagated and sold through multiple nurseries, as well as those that were grown and documented in more than one of the three time periods recorded (pre-1830, 1830-1869, and 1870-1907).

We found that, overall, 90% of the 150 highest priority cultivars are currently available as a result of conservation efforts in genebanks, private collections, and nurseries. Overall, it’s quite remarkable (and likely due in part to the longevity of apple trees) that these trees remain available, since the USDA National Plant Germplasm System Clonal Repository, where apple cultivars are conserved, wasn’t established until the 1980s. Cultivars that are not currently protected within genebanks but considered high priority were identified and suggested for inclusion in genebanks in the future. There were 51 high priority cultivars identified as possible additions to genebank conservation efforts, many of which may be available from the National Fruit Collection in Brogdale, England, and the Temperate Orchard Conservancy in Oregon.

This information will be useful for the many landholders who have historic apple trees on their properties. Identification efforts may make use of lists of historic cultivars to help determine identities based on either DNA fingerprinting or phenotypic traits.