Speaking of botanical gardens maintaining collections of crop diversity, this just in:

A large collection of Teosinte seed was recently transferred from Duke University to the Missouri Botanical Garden Seed Bank. Teosinte is the wild ancestor to modern corn and the preservation of its genetic material is important to corn research and supports the long term conservation of crop wild relatives. The collection includes seven different species in the genus Zea and will be stored in long-term freezer storage where it may remain viable for decades. We are in the process of accessioning, drying, counting and repackaging the seed for storage in the freezers.

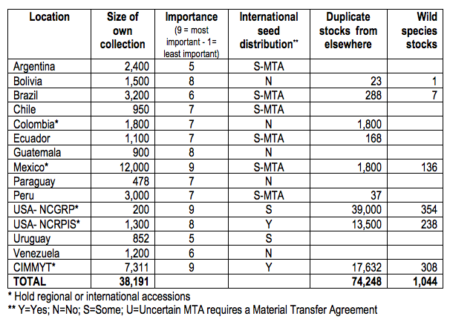

The Duke collection is not mentioned either in WIEWS or the global maize conservation strategy, so it’s a little difficult to know how important it is. Interestingly, there is a maize collection mentioned in WIEWS from North Carolina State University, and that’s not that far from Duke, but still. Any way you slice it, there aren’t too many collections of wild maize relatives out there, according to the global strategy:

It would arguably have been better for the collection to go to USDA, Ames (NCRPIS) or CIMMYT, but Rainer Bussmann, Director and William L. Brown Curator for Economic Botany at the Missouri Botanical Garden (MO) also made a perfectly good case for this option to me on Facebook:

Because we (MO) already had a (smaller) Teosinte collection, and we are housing a large corn collection, so this fit in perfectly.

So that’s another collection that the global strategy doesn’t know about. You can look for crop wild relatives on the PlantSearch database of Botanical Gardens Conservation International, but the secretive world of botanical gardens is such that this will only tell you that a particular plant exists in a garden collection somewhere, not which garden collection.

It doesn’t really matter where this Duke collection ends up, as long as it’s well taken care of, which it obviously will be at MO. But users also need to know where the stuff is, and get their hands on it. Isn’t it time botanical gardens and crop genebanks exchanged information a bit better? Rainer, how about putting the passport data on your new collection on Genesys?

Speaking of teosinte, there is at least one collection in Guatemala that doesn’t show up on the list.

Farmer organization Asocuch has done collection work with farmers and found a dozen or so Z. mays subsp. huehuetenangensis populations not documented by Garrison Wilkes and others before him.

I think this is a very interesting case of participatory PGR collection over several years (that will hopefully get documented). Perhaps this can inspire some of the CWR collection work that Kew Gardens and others are doing?

I also wonder if the missing teosinte collections say something about the incentives of being part of a network of collections with proper databases. Is there a clear benefit of putting the data in Genesys?

Is Genebank Database Hell not an issue of incentives and so on? Perhaps we need a concerted effort to put together some guidelines about citing accession numbers and convince editors to make them part of editorial policies. And provide academic citation credits to those who maintain the collections by making collections “citable” just like databases are becoming citable science products (e.g. journals like Nature Scientific Data).

That would solve both the sloppy use of accession numbers by the gene jockeys and provide clear incentives to make collection data available.

Probably I am not the first to suggest this?

And reflecting a bit more about the teosinte collection work done by Asocuch, we may need to think about motivation in citizen science projects — the question “What have genebanks ever done for us?” become quite important in relation to farmers. I have some suggestions for that as well: make a serious job of working in a citizen science mode.

We should stop thinking about these issues as a linear sequence (genebank -> breeding -> production) in which a particular breed of scientists are the protagonists (breeders and gene jockeys). And we should start thinking about this as a collaborative network that includes the farmers and in which diversity increase in value every time it goes around. The network would work because everybody has a different, complementary role and gets credited for the hard work that we all do. This should take us closer to a more sustainable use/conservation of PGR.

The linear model will always bite itself in the tail.