I do love a good historical counterfactual. Unfortunately, Henry A. Wallace becoming president of the USA in 1945 is not a particularly good counterfactual. You really want these things to hang on a coin toss, and it was in fact extremely unlikely that FDR would have chosen Wallace again as his vice-president running mate in 1944.

However, that didn’t stop me enjoying the recent episode of the podcast Past Present Future entitled “What If… Wallace not Truman Had Become US President in 1945?” Because of the erudition of the host David Runciman and guest Ben Steil, of course. Because Wallace was a pretty unique combination of politician, scientist and, well, mystic. But also because of a throw-away statement by Steil about half-way through to the effect that Wallace had sponsored a germplasm collecting trip to Mongolia while Secretary of Agriculture in the 1930s.

That sent me down a Nicholas Roerich-shaped rabbit hole. Roerich was also a very unusual character, “a Russian painter, writer, archaeologist, theosophist, philosopher, and public figure. In his youth he was influenced by Russian Symbolism, a movement in Russian society centered on the spiritual. He was interested in hypnosis and other spiritual practices and his paintings are said to have hypnotic expression.” Roerich undertook a number of expeditions in Asia, for example this one in 1925–1929:

The Bolsheviks assisted Roerich with logistics while he was traveling through Siberia and Mongolia. However, they did not commit themselves to his reckless project of the Sacred Union of the East, a spiritual utopia that boiled down to Roerich’s ambitious attempts to stir the Buddhist masses of inner Asia to create a highly spiritual co-operative commonwealth under the patronage of Bolshevik Russia.

That sounds plenty interesting enough, but the expedition that is most relevant here took place a few years later:

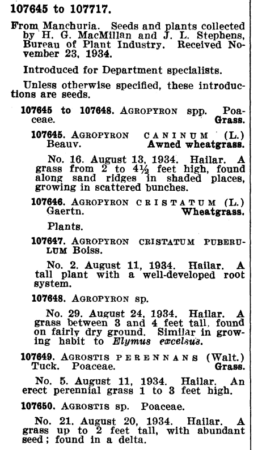

In 1934–1935, the US Department of Agriculture, then headed by the Roerich admirer Henry A. Wallace, sponsored an expedition by Roerich and its scientists H. G. MacMillan and James F. Stephens to Inner Mongolia, Manchuria, and China. The expedition’s purpose was to collect seeds of plants which prevented soil erosion.

The expedition consisted of two parts. In 1934, they explored the Greater Khingan mountains and Bargan plateau in western Manchuria. In 1935, they explored parts of Inner Mongolia: the Gobi Desert, Ordos Desert, and Helan Mountains. The expedition found almost 300 species of xerophytes, collected herbs, conducted archeological studies, and found antique manuscripts of great scientific importance.

A review of Steil’s recent book The World That Wasn’t: Henry Wallace and the Fate of the American Century summarizes that adventure thus:

Wallace backed the Russian artist and intellectual Nicholas Roerich’s expedition to Mongolia with government money. Scientists from the Agriculture department accompanied the trek to collect drought-resistant plants for study. Yet Roerich had his own nation-building ambitions. Soon, Cordell Hull, FDR’s secretary of state, complained about private adventurers and people from the Department of Agriculture intruding into a delicate region over which Stalin loomed.

Before long, the expedition’s quasi-political activities were getting bad press, too. Wallace felt betrayed by Roerich, and he smashed him. Steil does not report that Wallace asked the nation’s preeminent banker, Winthrop Aldrich at Chase National, to cut off every public and private means of funding to the Russian and his team, thereby stranding the travelers in the middle of nowhere.

Wrapping up this episode, Steil shows Wallace dodging criticism by writing a letter for the record: the Roerich expedition’s purpose was to find plants, nothing more, and surely not to create a cockamamie central Asian polity. This letter underscores Wallace’s “dishonesty and moral cowardice,” says Steil.

Be that as it may, the germplasm is still there in the USDA genebanks. And Wallace did a little seed diplomacy of his own later on. The days of US secretaries of agriculture personally exchanging seeds, or indeed facilitating foreign germplasm collecting trips with the potential side-effect of establishing cockamamie polities, are long gone. But collaboration on crop diversity conservation does have a lot of potential to bring countries closer together: all countries are interdependent for crop diversity, after all. Maybe it would be good if ministers of agriculture around the world followed Wallace and took a little more of a direct interest in seeds and genebanks.

Be that as it may, the germplasm is still there in the USDA genebanks. And Wallace did a little seed diplomacy of his own later on. The days of US secretaries of agriculture personally exchanging seeds, or indeed facilitating foreign germplasm collecting trips with the potential side-effect of establishing cockamamie polities, are long gone. But collaboration on crop diversity conservation does have a lot of potential to bring countries closer together: all countries are interdependent for crop diversity, after all. Maybe it would be good if ministers of agriculture around the world followed Wallace and took a little more of a direct interest in seeds and genebanks.