Luigi’s nibble of the keyhole gardens of Lesotho resonated with me for a couple of reasons. First, it showed that at least some people are not sitting about waiting for the rest of the world to solve the food crisis for them. More than that, though, it set me to thinking about this type of garden.

The BBC, with its customary ahistoricity, seems to think keyhole gardens are utterly novel and “home-grown” in Lesotho. Actually, they have a long history. I first came across them in a demonstration garden by Horticulture Therapy (now known as Thrive). They are round beds, raised to make it easy for people in a wheelchair to tend to the plants, and sized so that one can reach the middle of the bed either from outside the circle or from inside the slot that gives the garden its name. To be honest, I’m not sure who invented them. Permaculture practitioners often take credit for popularising the concept, but I’m sure I’ve seen earlier designs, including lung-like ones in which branching paths end in alveoli that allow access to the entire bed.

The point about keyhole type designs (whether raised for wheelchair users or not) is that they eliminate the need to tread on the soil, which is bad because it can lead to compaction and all the evils that brings. Keyholes, however, are just one manifestation of no-dig gardening. 1 The shape of the bed is immaterial; what matters is that you don’t step on it and that you don’t destroy the soil structure by turning it upside down once or twice a year. And no-dig of this sort is just one manifestation of very intensive horticulture. 2 And the weird part about no-dig, intensive horticulture is that it seems to be the child of affluence and self-sufficiency.

The poor, who need more than ever to be self-sufficient, have not generally been treated to these techniques.

It isn’t glamorous and it isn’t high tech, but it can deliver far more food than any other method. Not the calories of starchy staples, perhaps, although potatoes and other roots and tubers certainly do well in no-dig beds, but a wonderfully nutritious and satisfying diversity of fruit and vegetables. Furthermore, as the Lesotho example shows, there’s often a surplus to sell nearby.

One problem, I suspect, is that precisely because it isn’t high-tech and glamorous, intensive no-dig horticulture requires cadres of trainers. The system also needs to be tailored to people’s preferences and local conditions. I expect that the best way to propagate it would be to have demonstration villages that could train trainers and send them out into their world to spread the news. Wait a minute! Isn’t that something that Jeffrey Sachs’ Millennium Villages could be doing? 3 But I digress.

It seems to me, sitting here at the back of the Hall of Flags in the belly of the FAO beast, that widespread adoption of intensive, no-dig horticulture wherever poor people have access to at least a little land could do an enormous amount of good. There are opportunities for entrepreneurship and empowerment, and a prospect of real improvement. I just have no idea how to get something like that rolling.

The snatches I’m hearing from the statements and discussions (and I’m not privy to much corridor conversation) are all about high-yielding seeds and fertilizers (made from expensive oil) and irrigation. That package may have done as much good as it can.

Would it hurt to devote a small percentage of the millions being pledged to a different approach? Come to that, would anybody who is as appalled as I am about the same-old same-old being peddled as a solution care to bankroll something different?

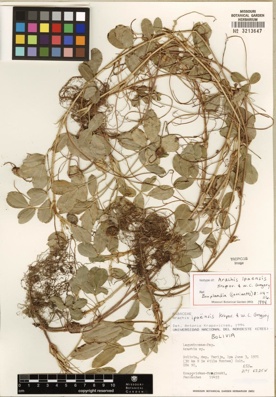

Well, that certainly adds a certain spice to an otherwise moderately routine story, I thought. So at the first opportunity I asked Luigi, who understands these things, to gbif A. ipaensis for me.

Well, that certainly adds a certain spice to an otherwise moderately routine story, I thought. So at the first opportunity I asked Luigi, who understands these things, to gbif A. ipaensis for me.