- Beer diversity to die for. Luigi comments: “Only 300?”

- Giant claims, some false, for genetic resources in North-East India.

- Coffee good for wild tree biodiversity. Joe unavailable for comment.

- How Alejandro Bonifacio saved quinoa. PROINPA comments: “And me?”

- Sheep manure’s contribution to Portuguese rye agriculture.

- Circum-Mediterranean escargotières.

- Map it or lose it.

Nibbles: GE, Grazing, Vanilla blight

- Broccoli’s goodies engineered into tobacco. Jeremy comments: “Let them eat broccoli”.

- Australians discover diversity: livestock graze grain (plants)!

- Unidentified blight strikes Malagasy vanilla: lack of diversity to blame.

Over-utilized crops?

Thinking about biofortification, I imagined a world that relies on fewer and fewer over-utilized crops. When will 95% of our food come from two or three of them? Perhaps a maize-arabidobsis hybrid, a cassava wunderroot, and super-rice? Shouldn’t we rather buck that trend and diversify agriculture? That message comes from several corners, like this one: “a food system that is good for us, our communities and the planet is small-scale, diversified agriculture.”

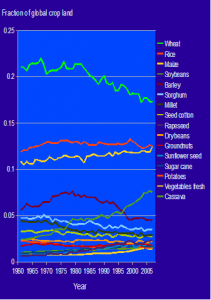

I checked 1 the FAO statistics to see how bad things are going. How quickly are we un-diversifying agriculture? If you consider the fraction of crop land planted to different crops, it appears that — at the global scale — the opposite of what I expected is happening. Between 1961 and 2007, maize and soybean area went up, but that was countered by the decline in the area planted with wheat and barley. 2 It is a story of both winners and losers, and — overall — an increase in diversity.

I checked 1 the FAO statistics to see how bad things are going. How quickly are we un-diversifying agriculture? If you consider the fraction of crop land planted to different crops, it appears that — at the global scale — the opposite of what I expected is happening. Between 1961 and 2007, maize and soybean area went up, but that was countered by the decline in the area planted with wheat and barley. 2 It is a story of both winners and losers, and — overall — an increase in diversity.

Global crop diversity, expressed as the relative amount of land planted to different crops, did not change much between 1961 and 1980, but is has increased since. Between 1980 and 2007, the Shannon index of diversity went up from 3.14 to 3.34.

Do tell me why I am wrong. Is it a matter of scale? Global level diversification of crops while these crops are increasingly geographically concentrated? Could be. Is the diversity index too sensitive to the relative decline in wheat? Perhaps. Or are we really in a phase of (re-) diversification, at least in terms of the relative amount of land planted to different crop species? 3 I cannot dismiss that possibility. For example, I have heard several people speak about on-going diversification (away from rice) in India and China. Has anyone looked at this, and related global consumption patterns, in detail?

Nibbles: mtDNA, Bison, Crises

- mtDNA inheritance not so straightforward after all. Everybody panic.

- Some bison herds more diverse than others. Care needed in genetic management of species. Well I never.

- It’s not a food crisis, it’s a crop diversity crisis.

Go forth and grow halophytes

That seems to be the plea Jelte Rozema and Timothy Flowers make in a Science paper that’s just out. 4 But, frankly, I found the paper disappointing, not least because it is short on clear recommendations. For example, what is one to make of this?

Because salt resistance has already evolved in halophytes, domestication of these plants is an approach that should be considered. However, as occurred with traditional crops such as rice, wheat, corn, and potatoes, domestication of wild halophytic plant species is needed to convert them into viable crops with high yields. Such a process can begin by screening collections for the most productive genotypes.

Are they telling us that domestication of new species is a more profitable approach than trying to breed salinity-tolerance into existing crops? I think so, in which case it would be an interesting view, but I’m not altogether sure that’s in fact the point they’re making. It could have been better phrased. I mean those first two sentences could be summarized as

Domestication of halophytes should be considered. However, domestication of wild halophytes is needed.

Not sure how the editors at Science let that one by. There was also no explicit reference in the paper to the International Centre for Biosaline Agriculture and its genebank. Or to the possible role of crop wild relatives in breeding for salinity tolerance. All around, an opportunity missed.