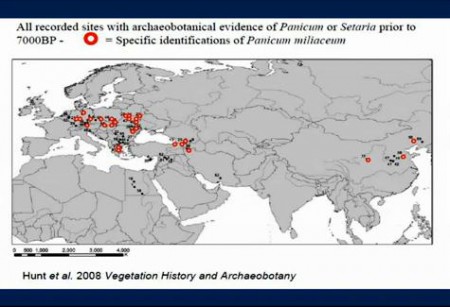

![]() Broomcorn millet is a bit of a puzzle. You start to get archaeobotanical evidence for cultivated Panicum miliaceum in both China and Europe at about the same time before 7000 BP.

Broomcorn millet is a bit of a puzzle. You start to get archaeobotanical evidence for cultivated Panicum miliaceum in both China and Europe at about the same time before 7000 BP.

Independent domestication or transmission along the fabled Silk Road (like wheat)? And if the latter, in which direction? You can hear the conundrum set out in more eloquent terms by the eminent archaeologist Prof. Colin Renfrew in this talk from last March, from which I’ve nicked the figure. You can just go to about 20 minutes in. But do yourself a favour and watch the whole thing.

Anyway, Prof. Renfrew mentions that genetic work is underway on Panicum which promises eventually to clarify the situation. And here it is. And, alas, interesting as it is, it doesn’t, not much. The paper in Molecular Ecology by Harriet Hunt and others looks at new microsatellite data on 98 landraces from across Eurasia obtained from genebanks in Russia, the US and Japan, and from new fieldwork in Inner Mongolia. 1

The researchers find evidence for two largely distinct genetic clusters, or genepools, one centered on China and one in Europe. And indeed of sub-clusters within each genepool. But they can’t use any of these data, even when combined with the archaeobotanical data, to distinguish between the separate domestication and Silk Road hypotheses. 2

The archaeobotanical and genetic data thus currently present a set of signals that are not wholly consistent with either a single or multiple domestication centres for P. miliaceum. Analyses to determine the direction of migration were uninformative for our data set.

Bummer. Ah, but there is hope: the wild relative!

The genetic picture would be clarified by comparison of landrace genetic diversity with that of the wild ancestor of broomcorn millet. Analysis of microsatellite diversity in P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale could determine whether this subspecies is indeed the wild ancestor of the domesticated form, in which case the former would be expected to maintain a more diverse genepool, or a derived feral type, whose genetic diversity is a subset of domesticated P. miliaceum.

So what’s stopping them?

We did not include any samples of P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale in the current study: Although morphotypes fitting the description of this taxon are reported as being widespread across the Eurasian steppe (Zohary & Hopf 2000), detailed information or samples are not easy to find. For example, P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale is not listed on the http://www.agroatlas.ru website, and no specimens are identified as belonging to this taxon in the extensive herbarium collection of P. miliaceum at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Appropriate field collections of weedy forms of P. miliaceum for genetic comparison with cultivated types are needed, but the necessary fieldwork across vast areas of Eurasia, to give a sample set from which reliable conclusions could be drawn, would require a major international collaborative project. Our demonstration of strong phylogeographic patterning in cultivated P. miliaceum makes fieldwork and sampling of P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale a high priority for further investigation.

Well, I know what they mean, but it’s not quite as bad as that. There are in fact 10 accessions labelled P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale in Genesys, originating from 8 countries and conserved in 4 genebanks in Europe and the USA. 3 Not a great haul, but a “major international collaborative project” has to start somewhere.

- HUNT, H., CAMPANA, M., LAWES, M., PARK, Y., BOWER, M., HOWE, C., & JONES, M. (2011). Genetic diversity and phylogeography of broomcorn millet (Panicum miliaceum L.) across Eurasia Molecular Ecology DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05318.x

- Actually, might not both be right? Might not simply the idea of domestication of this species travelled along the Silk Road, rather than the crop itself?

- Incidentally, those genebanks strangely don’t include ICRISAT’s. Need to check that.

One Reply to “Solving broomcorn millet”