A guest post from Fernando Aramburu Merlos on his recent paper with friend-of-the-blog Robert Hijmans.

Four species (wheat, rice, maize, and soybean) occupy half the world’s croplands. It has been argued that this means we cannot increase crop species diversity much without changing what we eat 1. Radically shifting our diets is a tall order, not just because changing habits is a challenge but also because we are so good at growing and processing the major crops. It’s an unfair race in which the major crops have a head start of millions of dollars and research hours.

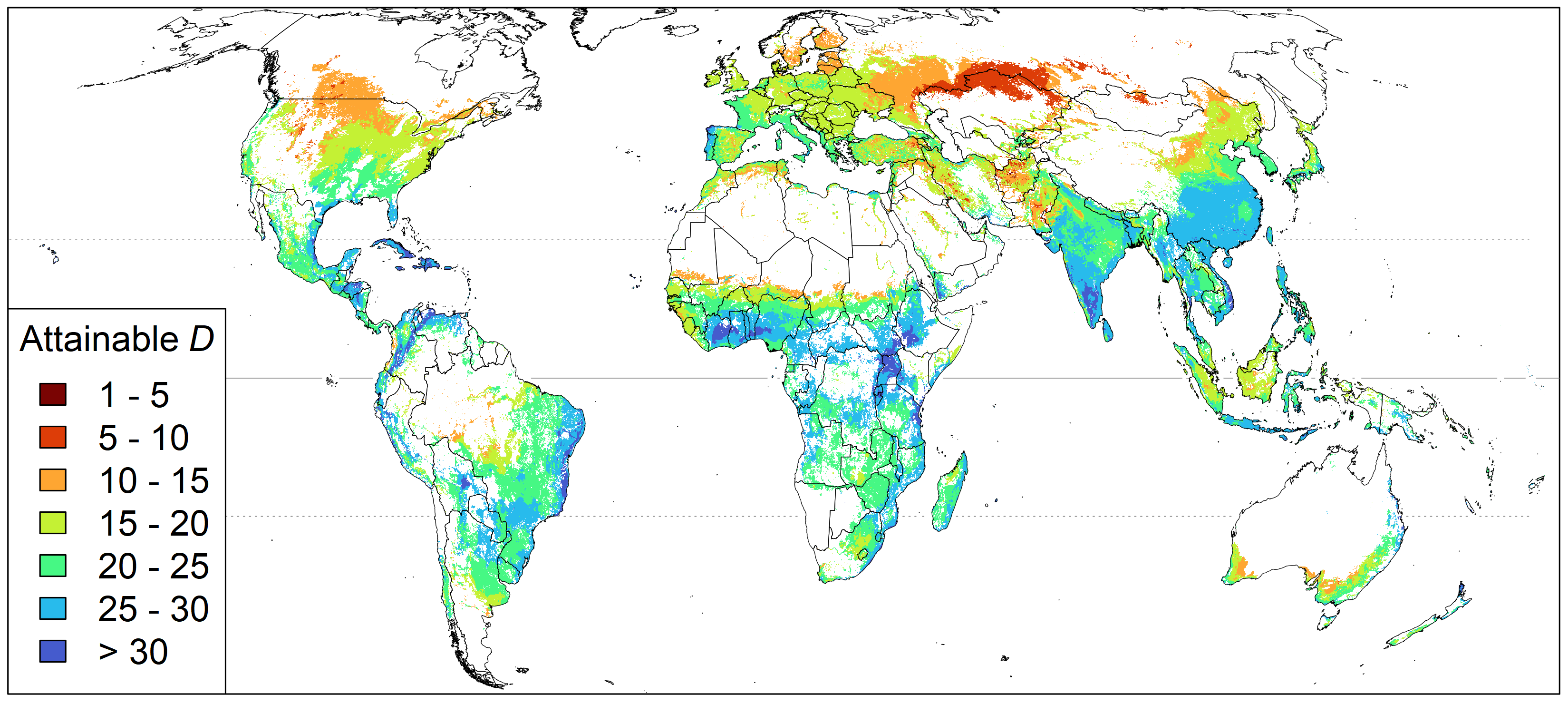

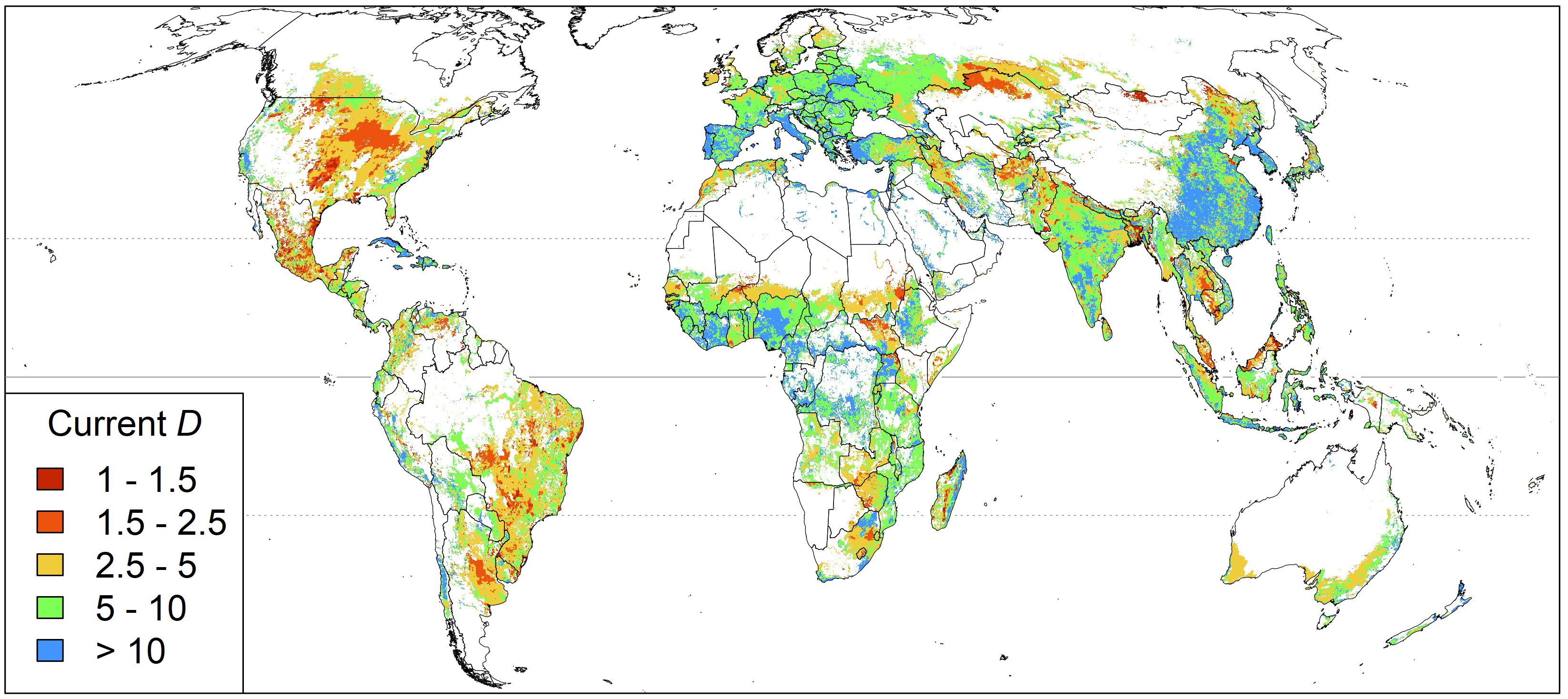

We wanted to know how much crop diversity can be increased without changing the global food supply 2. So we estimated the attainable crop diversity, which is the highest level of crop species diversity you can get without changing the total production of each crop. To compute this, we “shuffled the cards and dealt again”: over 100 crops were distributed across the worlds’ existing croplands by allocating each to the most suitable land while considering the inter-specific competition for land.

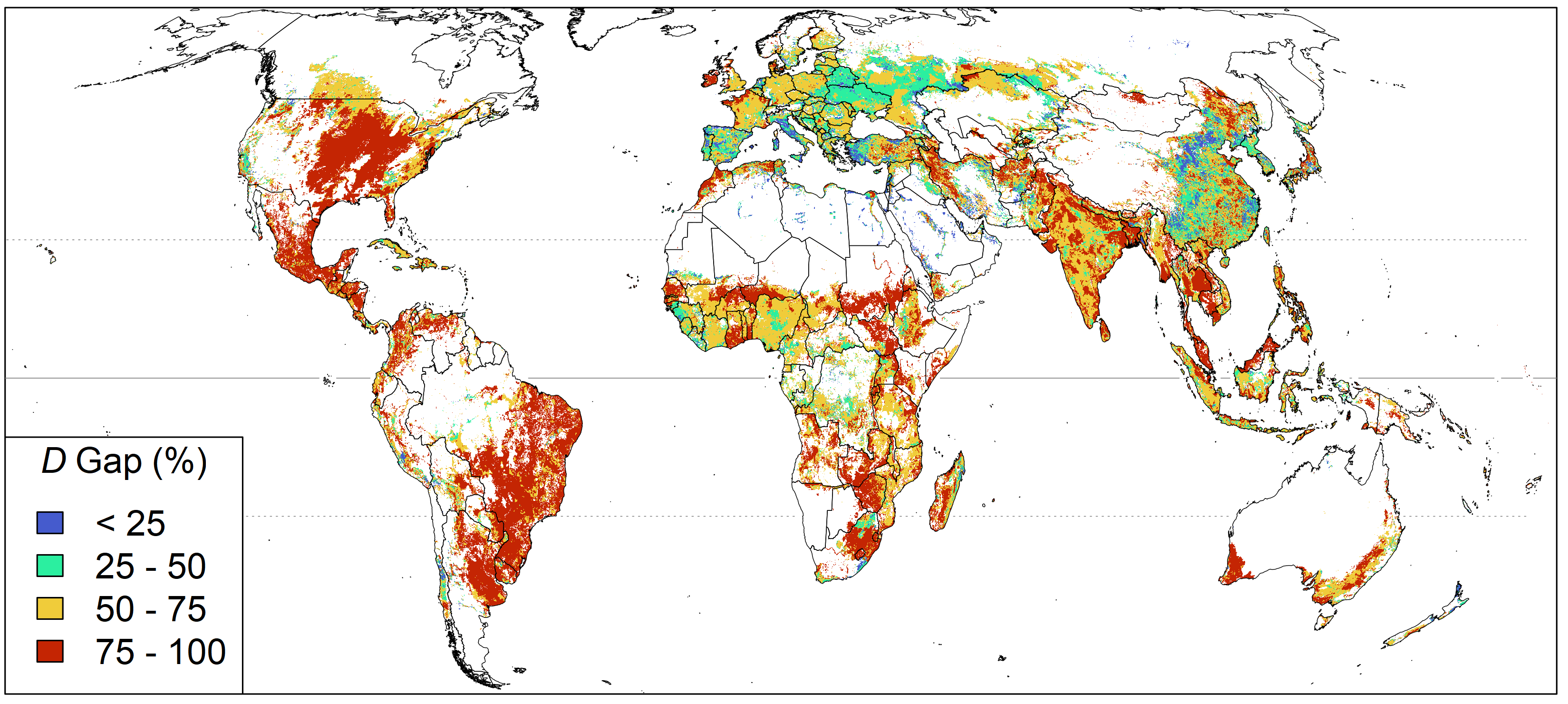

It turned out that tropical and coastal regions can reach much higher levels of diversity than temperate and continental areas. Perhaps that is not especially surprising, but one implication is that we should not assume that all countries can achieve the same maximum levels of crop diversity 3. We also noted that attainable diversity cannot explain current diversity patterns very well. For example, the diversity gap, the difference between the current and the attainable diversity, is much higher in the Americas than in Europe and East Asia.

Diversity gaps, expressed as a percentage of the attainable diversity, are greater than 50% in 85% of the world’s croplands. Thus, in principle, crop diversity could double in the vast majority of the world without changing our heavy reliance on a few staple crops. So there must be strong forces at work that make farmers and regions specialize. For example, at the farm level, a high crop diversity may be difficult to manage, reduce economies of scale, and be costly if it comes at the expense of the most profitable crops.

It would be interesting to better understand what specific factors limit diversification in the regions with the largest crop diversity gaps, and how to reduce them. But more important questions need to be answered first. How much diversity is enough diversity? And is that the same for all regions? Some very low diversity systems appear to be highly sustainable (the flooded rice systems in Asia come to mind). A more spatially explicit and species-specific, functional understanding of the effect of diversity at the field scale would be helpful. Without that, diversity gaps are just an interesting emergent property of specialization, but not something that necessarily must be reduced.

- Renard, D. & Tilman, D. Cultivate biodiversity to harvest food security and sustainability. Curr. Biol. 31, R1154–R1158 (2021)

- Aramburu Merlos, F. & Hijmans, R. J. Potential, attainable, and current levels of global crop diversity. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 044071 (2022)

- This assumption was made for the agrobiodiversity index proposed by Jones, S. K. et al. Nat. Food 2, 712–723 (2021)