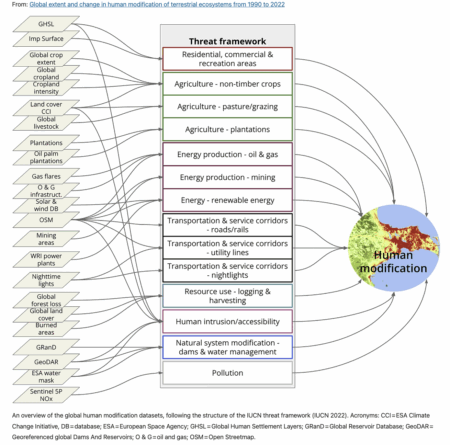

A new global assessment of the state of terrestrial ecosystems has just been published, focusing on the extent of human modification due to “industrial pressures based on agriculture, forestry, transportation, mining, energy production, electrical infrastructure, dams, pollution and human accessibility.” 1

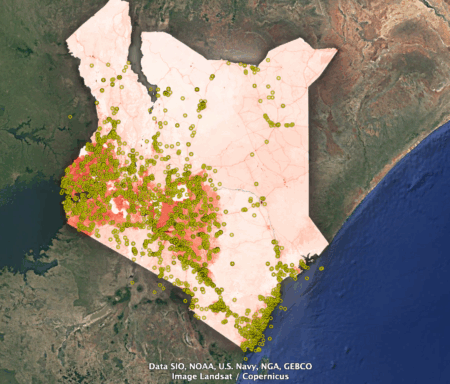

As is my wont, I tried to find a form of the data that I could shoehorn into Google Earth, but I failed. Fortunately GIS guru Kai Sonder of CIMMYT was able to snip out a kml file of overall human transformation as of 2020 covering Kenya — don’t ask me how. But thanks, Kai. I put on top of it genebank accessions from Kenya classified as wild or weedy in Genesys.

I don’t know quite what to make of this. The wild populations seem to have been mainly collected in areas that in 2020 were very highly affected by human activity. But is that good or bad?

It could be good — in a sense — if the high degree of human transformation means that the original populations are not there any more. 2 Phew, good thing they were collected! On the other hand, it could be bad if the concentration on easily accessible and modified areas means that the genetic diversity currently being conserved is not representative of what’s out there.

What do you think?

But of course what I really want is a version of this which focuses on agricultural areas and is updated in real time. Yes, a perennial favourite here: a real early warning system for erosion of crop diversity.

- Theobald, D.M., Oakleaf, J.R., Moncrieff, G. et al. Global extent and change in human modification of terrestrial ecosystems from 1990 to 2022. Sci Data 12, 606 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-025-04892-2

- Or have lost genetic diversity. Incidentally, there’s a group that’s trying to monitor that from space.

One thing is that when a lot of this was collected I would assume that larger parts of Kenya were still in less disturbed shape. Also the more undisturbed parts of Kenya are rather dry so not so many crops and wild relatives around?