We are extremely grateful to Ove Fosså, President of the Slow Food Ark of Taste commission in Norway, for this contribution, inspired by a recent Facebook post of his. We hope it is the first of many.

Beer is a fermented beverage usually made from just water, barley, hops and yeasts. That simple recipe can, however, produce a large variety of beers, and can harbour an immense range of biodiversity.

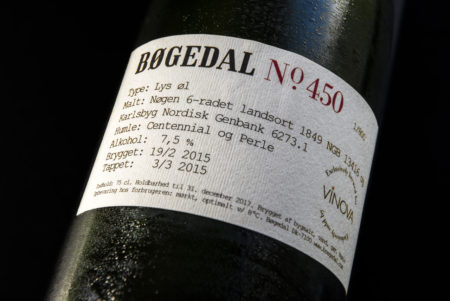

Bøgedal Bryghus is a small Danish brewery located at the idyllic 1840s Bøgedal farm. The brewery was established in 2004 and makes around 30,000 bottles per year. Each batch of around 800 bottles is different, and the batches are numbered, not named. Some of Bøgedal’s beers are made from heritage barley, sourced from the Nordic Genetic Resources Center. This barley is grown on a neighbouring farm, and malted in Denmark. They take great pride in using heritage varieties. The beer labels list both the variety names and the genebank accession numbers.

‘Chevallier’ barley provided some of the best malts and was one of the most popular varieties up until the 1930s, when other more productive varieties took over. It has been revived recently by the John Innes Institute, and used to produce a limited edition beer, the Govinda ‘Chevallier Edition’ IPA by the Cheshire Brewhouse. According to the brewer, it…

…is NOT a beer that’s about in your face HOPS! Quite the opposite, it is a beer that has been brewed to try and replicate an authentic 1830’s Burton upon Trent Pale Ale, and I have tried to manufacture it to an as authentic a process as I can, so as to try and replicate an authentic Victorian beer!

There are other beers using heritage ingredients, but they are few, and hard to find. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault has 69,000 accessions of barley as of today. Relatively few of these will be suited for malting, but still, the potensial for variation is huge.

Few beers advertise the variety of barley used. More often, you will find the name of the hop varieties on the bottle. Hops have not changed much over time, and many old clones are still in use. ‘East Kent Goldings’ has been around since 1838 and is the only hop to have a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). Hops cannot be reproduced reliably by seed, and are kept in clone collections. The Svalbard Seed Vault has only 18 seed accessions of hops. The USDA/ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository (NCGR) has a field collection of 587 accessions of hops and some further accessions in a greenhouse collection and a tissue culture collection.

An often neglected aspect of biodiversity is the diversity of microorganisms. In beer production, this is mainly brewer’s yeast. Many, probably most, breweries today use commercial yeast cultures, and are more concerned with standardisation than with local character.

Norwegian breweries have mostly copied foreign beers and thus also started out with imported yeast cultures. These eventually evolved into specific strains which are now guarded by their owners, and master cultures are stored at the Alfred Jørgensen Collection in Copenhagen, now owned by Cara Technology Ltd. They have a collection of 850 strains of brewing yeasts. The National Collection of Yeast Cultures (NCYC) in the UK holds over 4,000 strains of yeast cultures, including 800 brewing yeasts. The American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) holds more than 18,000 strains of bacteria, 3,000 types of animal viruses, 1,000 plant viruses and over 7,500 yeasts and fungi.

Wild, or spontaneous, fermentation is quite trendy in winemaking today, producing ‘natural’ wines with local bacteria. In one area of Belgium, spontaneous fermentation never went out of fashion. From the Pajottenland west of Brussels comes lambic and gueuze, ‘sour’ beers, in some ways more similar to wine than to other beers. Wild fermentation can never be reproduced faithfully by commercial strains of microbes because of the diversity.

In Norway, a project to collect information on local raw materials for beer production was started in 2012. The focus is on barley varieties and hop clones, but wild herbs are evaluated, too. So far, no beers seem to have come out of this. The project does not take yeast cultures into account. Luckily, some home brewers work with local starter cultures, called kveik (literally kindling). Commercial breweries are following. The Nøgne Ø brewery has just released Norsk Høst (Norwegian Autumn), a beer based on Norwegian ingredients only, including kveik, spruce shoots, and bog myrtle. But, alas, the malt seems to be from modern barley.

Anything to do with beer is grist to my mill – We’re off to the Scottish beer Festival tomorrow. BUT the `just water, barley, malt, yeast’ is old hat – the old German Beer Purity Law (Reinheitsgebot) that makes beer in Germany a bit drab. There is a good commentary on this here.

These comments: “Virtually none of the classic Belgian ales is, or even can be brewed if you stick to the rules of the Reinheitsgebot. Framboos and kriek because of the use of fruit (hardly a cheap replacement for malt), La Chouffe and witbiers because of their use of spices. None of these would be possible. Given the choice between Heineken Pils and La Chouffe, I know which I would go for.” and “What is really needed is legislation forcing brewers to list the ingredients on the label (as is already the case in Scandinavia).” Good for the Scandinavians – as with the bottle you showed. The Bodegraven beer festival each September is a must for me and last year there were lots of excellent beers from the countries all round the Baltic.